Lian Lunson is an acclaimed documentarian, editor, and film producer. For her 2005 documentary film Leonard Cohen: I’m Your Man, she was awarded the Dorothy Arzner Directors Award by Women in Film. Her latest work, Sing Me The Songs That Say I Love You: A Concert for Kate McGarrigle (2012), is a record of a 2011 tribute concert to the late Canadian folk legend Kate McGarrigle. The film features performances from McGarrigle’s children and executive producers Rufus Wainwright and Martha Wainwright, as well as from McGarrigle’s sister Anna, comedian Jimmy Fallon, and a wide assortment of singers and songwriters. Sing Me The Songs was an Official Selection of the 56th Annual San Francisco International Film Festival, held in May 2013. Ms. Lunson spoke with Sean Malin of CineMalin: Film Commentary and Criticism about her former life as a dramatic actor, the templates from which her film drew inspiration, and her intense relationship to the McGarrigle and Wainwright clans. This interview has been transcribed, edited, and compressed from audio for publication.

Sean Malin: Your film has been screening for audiences around the world. Have you been pleased with the reception to it?

Lian Lunson: It really connects with people, but not with everybody. I don’t know that it is everyone’s type of film at all, because some people think it is just a concert film and are taken aback by the rest of it. But for some, it strikes them very deeply, and I always make my films for those people.

SM: Specifically, for people who you think might have a profound reaction to it?

LL: Who will have an experience. Not everyone is capable of that, or rather, not everyone is going to find that in the film. Often it will go over somebody’s head or it will not resonate with them. But I’ve made it for the people who will take it to the deepest place.

SM: You started as an actor. When you were performing, did you choose your projects in the same way?

LL: No. I was in Australia and had just been to drama school; at that point, you take anything and everything and are happy to be working.

SM: Did you train at N.I.D.A. [National Institute of Dramatic Art]?

LL: I was at The Ensemble, which is no longer [in Australia]. It was a great, great school, a Stanislavski method school. I did a lot of theatre and a couple of movies that were pretty terrible. But, you know, I grew up in the middle of nowhere and I loved movies. I thought that you had to be an actor to be in them. I didn’t think that I could make them. So that’s why I got into acting before I realized I actually preferred doing the other stuff *laughs*.

SM: How long into your career in entertainment did it take you to realize where your interests laid?

LL: When I first came to America, I started working with a production company, where I learned how to do budgets and all sorts of production work. Once I realized I had the tools to get something done – and also had some sort of creative vision – it became very exciting for me to recognize that. Getting those tools is ninety percent of the challenge, really.

SM: Do you mean technically? Like, physically getting things done?

LL: Oh, absolutely. My first job came from someone at a record company wanting to do something with Willie Nelson. And I was the only person who could do it for the amount of money they had. I happened to be a big Willie Nelson fan and knew a lot about him, and I made what I think is a beautiful piece on him. For some people, they are good with budgets but maybe not so creative, they are typically one or the other. I happen to be more on the creative side [of filmmaking], so I was able to say I could do this creatively, while also knowing how to get it done technically.

SM: You mentioned being good at budgeting. I imagine that in your field of work, documentary and concert filmmaking, that’s a pretty necessary skill.

LL: I do think it’s necessary! I’m always struck by filmmakers who are not involved with their budget in any way or just have a producer who deals with it. At the end of the day, that producer can come over and say, “Wow, you know, we can’t do this shot because we don’t have the time or the money.” Without the ability to look at that budget and say, “I can take [this amount] from here and put it there,” you lose power. It’s a no-brainer for me – I would think people would want to be able to say that to their producer.

SM: Without trying to make you or anyone sound like a dictator, being the director of a film does place you into a position of power, and sometimes creates authorship even if the film is a collaborative work. Have you found that, by taking the reigns of your budgets and moving them directly toward what you’ve described as your creative vision, that your job as a filmmaker has become easier?

LL: Well, I’m not the sort of person to walk away from a project when there’s not enough money. I find [the budget] and do it. As an artist, you tend to do what is necessary for that film. I think people can often organically sense that you have done whatever you needed to in order to get it made. Sometimes it’s in the way you shoot it. I’m a big fan of 70’s concert films, many of which didn’t have all this fancy equipment or cut like the MTV generation. Those films felt so real and so organic because, you know, they shot very close, they didn’t have cranes and all these things. I’ve always liked to feel like I’m there and have always tried to work in that way. I’m lucky because that has always seemed to work in my favor. I do not like to work with a lot of equipment or “stuff.”

SM: Talking about concert films in the seventies, the first thing that comes to mind in a significant way has to be The Last Waltz (Scorsese, 78).

LL: Of course, as well as Mad Dogs & Englishmen (Adidge, 71), Concert for Bangladesh (Swimmer, 72)…

SM: Bangladesh and The Last Waltz have one thing in common that seems mildly contrary to what you’re saying: this attention to lighting and the four major cinematographers on Waltz, like Michael Chapman and Laszlo Kovacs. Your film achieves a similar effect, I think, but you work intentionally on a much smaller scale than those films.

LL: That is a compliment, as that’s what I am trying to do. Often these days, particularly in concert films, they tend to use so many cameras and all of these gadgets, and I just think it is waste. One of the things I learned in producing was what not to do with money and equipment that would just become waste. A lot of times someone would get everything they could because they didn’t know what, specifically, they wanted to do. But you don’t need backups if you know what you want your film to look like.

SM: Were you involved in arranging the Concert for Kate, or were you brought in —

LL: I did it from scratch. I was there from Day One and did all of it.

SM: Lighting for the concert, logistics for everyone appearing, and budgets?

LL: Yes.

SM: Is that an enormous task?

LL: In these venues…On the Leonard Cohen film (2005’s Leonard Cohen: I’m Your Man), I was not even allowed to be in the [Sydney] Opera House where we shot. I had no control over the lighting at all; it wasn’t lit for film or anything. I was basically there as a voyeur for a Sydney Film Festival event and had to do the best I could in that circumstance. In this case, we were putting on the concert for a film audience, which I’m quite sensitive to. I don’t like to feel like I’m in the way or that the cameras stand out at all. I try to make myself invisible. And you don’t have much control of lighting, anyway, in these sorts of venues. Sometimes you can ask for a little favor with a light here or there. I think it must be much harder on the type of concert film in which the audience and every thing onstage has been carefully arranged. Those filmmakers often have to find “that shot,” whereas I’m in search of something much more organic.

SM: How long after Kate’s death [in January 2010 to clear-cell sarcoma] did Rufus and Martha [Wainwright] contact you?

LL: I think it was just a bit less than year when I heard from Rufus.

SM: Was I’m Your Man when you and Rufus first came into contact?

LL: Exactly, yeah, and I met Kate then, too, because she was in that concert. Ironically, I believe the first time she thought something was wrong was on the plane ride to Sydney for that concert. So it was sort of weird to be coming back and working with the family again under those circumstances.

SM: It sounds like you had a real, qualified relationship with your subject and her family. If that’s the case, why would you want to make yourself invisible in the film? For example, you could have included interviews between you and her or you and the subjects.

LL: I just don’t think I’m that sort of filmmaker *laughs*. I do think that kind of film has its place. But my subjects are so large, and the atmosphere of their lives or deaths fills the rooms. In those situations, I think you only have time for the people who are closely involved in that atmosphere. It might be different if I were making a film about a very close friend of mine, but not in a situation that requires you to pay homage to the world that you’re in. It doesn’t include me in that way.

SM: Were Rufus and Martha supportive of your creative vision for the film?

LL: Very much so. It helped that we had worked together on the Leonard Cohen film. I think they trusted my approach in how to get things done. They know the way I shoot: very close, very still. We had stayed friends and seen each other over the years since that film. This was also something we had to put together very quickly, so it helped that they knew how I shot.

SM: Right – weren’t you in preparation on a project in between I’m Your Man and Sing Me The Songs?

LL: Yes, I was writing a script of a film I tried desperately to get made but couldn’t because the industry was going through so many changes. I had attached big names and prepared everything, but I still kept hitting a wall. I will get it made, though.

SM: You have an IMDB credit with several question marks next to it and Christopher Walken’s name.

LL: He was attached with Shirley Maclaine, yeah.

SM: That’s outrageous. How does something like that not get made?

LL: I know! *laughs* And it’s a good script, too, so it will get made. But when Rufus asked me to do this, I just put that script aside – it just seemed like the right thing to do. I worked too hard not to get it back up off the ground and get it going, yet I couldn’t miss doing this project, even if it took me all my time.

SM: Help me create the timeline in which this film was made. You’re contacted by the Wainwrights after the tragedy. Then, how much time did you have and what did you begin organizing to get the film made?

LL: Rufus and I were at a dinner and he asked me some questions about what it would take to get a film made, how the logistics worked, things like that. Later that week we met again and he burst into tears, then I burst into tears…and we both knew then that I had to make the film.

SM: And how long from then did it take you to organize everything for the concert [“A Celebration of Kate McGarrigle,” May 12 and 13, 2011]?

LL: Not long, actually – maybe a couple of months? When I decided to do the film, the concert date had already been set as both a tribute to Kate and as a Kate McGarrigle Foundation event. We started out with Rufus asking me how I might go about filming the concert since they already knew it was happening. So I went set about raising funds for [the feature}…and then just did the editing out of my house in my living room.

SM: How has the distribution process been for this film?

LL: Well, in addition to editing it, we’re self-distributing the film as well. Our first outing will be at Film Forum in New York City [beginning June 26, 2013], which is big and good. My Leonard Cohen film opened there, too. We’re also going to be on Video-on-Demand through Sundance Platforms, which I’m very excited to be a part of.

SM: Has the film been shown to American audiences, aside from the San Francisco International Film Festival?

LL: We had a low, low-key screening at the New York DocFest. They had just gone through Hurricane Sandy and we didn’t have any press or anything. We just, pretty much, invited our friends and Rufus’s friends to it, and kept it under the radar. In addition to being Sundance alumni, we did screenings in London, Sydney, Berlin in February, and we’ll do Seattle after San Francisco.

SM: Has that been enough to get a foothold in with audiences from the folk generation? I would hate to use the word “market” in terms of reaching out to them…

LL: I don’t think we’ve been out enough yet for that. There are people from that group who have seen it, but they tend to be Kate McGarrigle or Rufus Wainwright fans anyway. The strongest reactions we’ve gotten are from people who are unfamiliar with her work. You know, she put her career on hold in a big way to raise her children, but the film really showcases her songs. My hope is that the people who don’t know much or anything about Kate McGarrigle will come to love her music and be turned on to it. I tend not to make films for fans [of the subjects] because you know the fans will see it anyway, no matter what. We’re trying to reach out to a new audience who don’t know this woman who wrote these incredible lyrics, or Leonard Cohen, this poet who still makes music. Those are the people who come up to me after the films most.

SM: Last year, Malik Bendjelloul’s Searching For Sugar Man (2011) begot a sort of second Renaissance for another folk poet. Sixto Rodriguez’s entire life has been changed by the success of that film. Given that movie’s success, do you imagine that your film could have that effect on Kate’s legacy?

LL: You have to give as much life to your films as you can, and then just let them go. It sounds cliché to say, “if it turns just one person on” or “touches one person in some way,” but that’s my job. You want that to happen to many people. Someone like Rodriguez was so talented and powerful that people had a vague memory of hearing his songs. Everyone I know was like, “I think I remember hearing that somewhere!” That was the beauty of that film.

SM: What is it about folk poets – Willie Nelson, Leonard Cohen, Kate McGarrigle – that particularly draws you?

LL: I’m not actually drawn to folk poets in any real way. I did the film on Leonard Cohen because he is Leonard Cohen. I could not define him as anything other than Leonard Cohen. For Kate, I initially did the film because Rufus asked me to do it, and because these are incredibly talented people. They aren’t just pop stars or commercially marketed [entities]; they are pure, raw talent. THAT is what interests me and what I connect to in my subjects.

SM: Do you think working with a pop star or commercial entity on a concert film means sacrificing that real drama, that organic quality you’re in search of? For example, in Kenny Ortega’s This Is It (2009) or Katy Perry’s Part of Me (2011) – though they may be deep documentaries, do they lose something in trying to represent popular culture?

LL: I don’t actually know how well that works, and I’ve not watched anything like that. But I am not a big believer in spilling out all your information on reality TV or in “Behind the Music” sorts of things. They are great, but sometimes less is more – I’m far more interested in trying to capture the energy of a person and the atmosphere around a person than in what they ate yesterday or whom they dated. If it’s possible to tap into that otherness, that quality, that makes them so talented and great.

SM: Tell me a little bit about Wim Wenders’s [the film’s executive producer] involvement.

LL: He’s been my mentor now for years and is a very close friend. In some way, he’s been involved in all my films, whether in the editing room or just talking with me about them. He’s of course an incredible filmmaker and I was a huge fan for many, many years. I was so lucky to have met him, and we became friends. He had come to my house to visit while I was assembling the footage before anything had been cut. He saw it and he said, “Wow, if I can do anything or be part of this film in any way…”

SM: What did he end up doing on it?

LL: He watched the film a couple times and spoke to me about it. He didn’t do physical work but that really doesn’t matter. When you have someone like Wim Wenders and he wants to lend his name to make it a “Wim Wenders presents” film, that’s a big honor. It’s like Scorsese lending his name to younger filmmakers or producers these days, and Wim is very much on that level for me, particularly in music films. Having his name attached meant a lot to me and to the family, too. After he came onboard, he met up with Rufus in Germany and saw Martha in Berlin. They had known each other a bit, but Wim was already a big fan of their music, you know?

SM: Because he’s not busy enough [Wenders released 2011’s Pina and Mundo Invisivel in 2012].

LL: That’s part of the reason he didn’t do more on it, because he was so busy. He wanted to get involved, but he had Pina coming out for the Oscars and was just so busy. But I try to get him involved with everything I can because he’s, you know, a legend. I definitely want people who aren’t familiar with him to go, “Who’s Wim Wenders and why is he working with the Wainwrights?”

SM: It must be hard to feel good about a film that commemorates a tragedy. That being said, have you found that the wide range of people you worked with to get the film made are satisfied that it does justice to the life of Kate McGarrigle?

LL: I cannot at all speak for the family. And there are multiple films you could make about Kate McGarrigle’s life, or Kate and her sister Anna, the career of the McGarrigle Sisters. There’s her relationship with [former] husband Loudon Wainwright III. My film really focuses on this concert and her children. I could not have fit them all in and do a concert film as well. Rufus and Martha were my focus in this film, but there’s so much more to her life and to her career that I just was not able to touch on. My job, my main goal, was to capture the emotion and energy at this particular concert, and that is something that I do in the film. There are times where you’ll watch a concert or seeing a documentary of footage where you think, “Wow, that is nowhere near as good as being there.” Whereas I sought to make sure that people who may have seen the concert and then see the movie think the movie is better. And if not, that people feel like they were there during that experience.

—

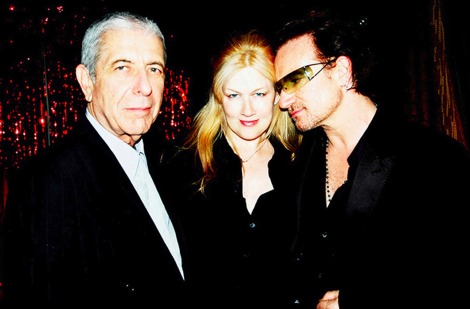

Editor’s Note: Following our interview, Ms. Lunson generously donated the following exclusive clip from Sing Me The Songs That Say I Love You: A Concert for Kate McGarrigle. The short-format trailer explores several of the film’s most beautiful sequences. Sean Malin and the transcribing editor(s) of this piece would like to thank Ms. Lunson for this striking clip, and for various still images in the above interview.