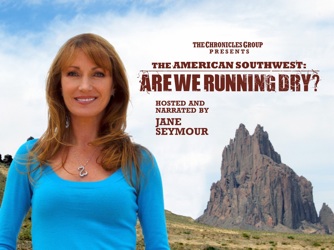

Jim Thebaut is an award-winning journalist, producer, and documentary filmmaker. Mr. Thebaut rose to international recognition after his interview with convicted murderer Richard “The Iceman” Kuklinski was the subject of his documentary film, The Iceman Tapes: Conversations With a Killer (1992). His film was one of the key sources of the 2012 feature film The Iceman, starring Michael Shannon as Kuklinski. Mr. Thebaut’s current project, Running Dry: Beyond The Brink, delves into the realities of water scarcity, drought, excessive population growth, and its ultimate impact on international security, themes he began to explore in his 2005 documentary Running Dry and continued with 2008’s American Southwest: Are We Running Dry? In addition to his services as a filmmaker and journalist, Jim Thebaut is the president and CEO of the Chronicles Group. Mr. Thebaut spoke with Sean Malin of CineMalin: Film Commentary about his responsibilities as a producer and social-issue documentarian, whether he considers himself a journalist or a filmmaker first, and the upcoming subjects of his new project. This interview, conducted in June 2013, has been transcribed, edited, and compressed from audio for publication.

Sean Malin: Why do certain social issues make their way into documentary films en masse, while other topics just fall by the wayside?

Jim Thebaut: Most documentaries, the ones that receive the greatest attention, are oriented to subject matter that has to be provocative and relevant. Getting attention is all about access. If you don’t have the access to a person or an entity – like, for example, Alex Gibney’s new film We Steal Secrets: The Story of Wikileaks (2013), or when I did [The Iceman Tapes], and I had access to the actual Iceman, to his wife, to the cops – that can have a great deal to do with your marketability.

SM: But isn’t it sort of depressing that, when making a project, you have to be in touch with what we consider our markets or our channels?

JT: You always have to do that, even though they change a lot. I know that HBO [who premiered The Iceman Tapes] knows its audience well – they will only buy things they know to be relevant to that audience. If you’re going to release a film theatrically, you have to realize, “Okay, the general public will or won’t gravitate to this story.” It is all about your audience, your access, and your marketing. You have to market.

SM: Do you think that documentarians without the same experience that you have as a producer struggle more with the issues involved in marketing?

JT: Well, they must because there are thousands of those documentaries produced every year that never see the light of day, you know?

SM: I think that’s what distresses me: that a filmmaker who doesn’t keep marketing in the back of his or her head is destined not to find an audience for the film. You have been making films about water scarcity and drought for years now. Do you think there are significant groups of movies on the same subject that just don’t find their way to audiences? Or is it the other way around – not enough films despite the possible viewers waiting in the wings for the right film?

JT: I do not think enough films are made about water, at least not on my radar. But one thing I have noticed ever since I produced Running Dry is that organizations seem to have sprouted up everywhere on the subject of water. The film was made in 2005 and had its initial screening at the Russell Senate Building on Capitol Hill. It had a powerful impact on generating foreign policy legislation as well as creating a ripple effect on grassroots citizen involvement. It was the genesis for the Senator Paul Simon Water for the Poor Act, which then passed in record time. It went right through the Senate and the House of Representatives; no one had ever seen anything like it. I think that’s mainly because [the Act] transcends political ideology. Consequently, it’s important for documentary filmmakers to realize that, if strategically targeted, their films can make a huge difference in educating the world. More recently, however, there’s been an attempt to put forward the Paul Simon Water for the World Act (2011), which is having greater difficulty in the current political climate.

SM: Do you think when a film details a subject that is difficult or impossible to legislate on, like water cleanliness and scarcity, that the film is similarly difficult or impossible to make? It seems, by contrast, that films about electricity or electric transportation hit theaters every few years.

JT: Most people don’t really think about water in the United States, we just take it for granted. Turn on the tap, and usually you get drinking water. With electricity, however, you get a brown-out and it really affects your psyche. I remember one time I was in South Africa, just watching a movie in my hotel room. Suddenly the TV went out and so did the lights. This sort of issue happens a lot in South Africa and it’s something they deal with in India, too. It’s all about your security or the lack thereof based on where you are. That almost never happens with water in this country. I think that’s one of the main reasons people don’t keep water on their radars. When I first started promoting Running Dry around the United States, people did not seem to relate to it at all. They’d say, “Well, that’s over there but not here.” That reaction caused me to produce [and write and direct] American Southwest: Are We Running Dry (2008) just to bring [the issue] home.

SM: You’re in process on a new film in the Running Dry saga, Beyond the Brink. What’s the focus of that project?

JT: It will be a different film from the others because I will be focused on other parameters. I will be talking about water scarcity, but also about climate change, drought and its relationship to public health, energy, education, agriculture and the food supply. We’ll have ten billion people on the planet by 2050 or ’60, so population growth will be there, too, and its impact on international security.

SM: On a documentary of that scale, what is the production process like? How many cameras do you need? Where will you have to go?

JT: The production activities will be significantly more comprehensive and complex than any of my previous films on the subject. I will be going to places that are not normally on the tourist agenda *laughs*.

SM: So, not Zurich, Switzerland?

JT: *Laughs* Regrettably, no, I don’t see Zurich on the agenda. I will be going to places like the Horn of Africa, Yemen, locations in the Middle East, Pakistan and India. Places where the potential for conflict is much more severe.

SM: Aren’t you the head of an accredited non-profit organization?

JT: Yes, a 501(c)(3).

SM: So how do you intend to raise enough money for a project of this size?

JT: I do not intend to through the non-profit. I’ve actually set up an LLC and will raise money as a for-profit venture. That’s my objective. In today’s economic climate, it’s very hard to raise the kind of money needed for this film’s budget.

SM: Will trying to raise money for Beyond the Brink as a for-profit feature mean sacrificing autonomy in any way?

JT: That is not an experience I’ve had thus far [in my career.] I have had total control and final cut on every film I have ever done. That said, I always open the filmmaking process to others, just as I did when I was an environmental planner. In my previous incarnation, as I call it, I used to write environmental impact statements and planning studies. Well, every time I would prepare one of these studies, I would get people to review it so that, by the time it got to the light of day, it had already been put through the review process. As a journalist, I do the same with my films – I want to make sure that the content of my films will not be questionable; that the facts and figures are as accurate and truthful as they can possibly be; that the film has credibility. The opening-up process does not just include having a colleague or two review the script before I head into the editing room. I also have rough-cut screenings with people who are experts.

SM: And even though there are some times relatability issues with the general public, screenings with the experts typically go well?

JT: I think [the screenings] are essential. I remember three. We had one at the Springs Preserve in Las Vegas, which had this beautiful theater; one just outside of Albuquerque at a Native American conference that was attended by engineers and scientists from all across the American West; and one at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington, D.C. By the time I had put the film through THAT process, I was able to take the time I’d left for myself to go back into the editing room and take out any of the existing problems.

SM: You describe yourself as a journalist. Do you consider yourself more of a journalist who uses films as the medium for research, or are you a filmmaker with an investigative journalism background first?

JT: I have always thought of myself more as a journalist. I don’t consider myself a great filmmaker, but there are really great documentary filmmakers and producers. My films are marketable and have done real business, but I believe people are more attracted to my work because they believe it. I try not to editorialize. Now, I have biases – for example, saving children. I have to admit that I have a bias towards them…

SM: You want to preserve the lives of children? *laughs* Me too!

JT: *Laughs* Saving children, yes, I do. And if I should be up for questioning on that subject, then so be it. But the fact is that when I have to access statistics, I check ‘em out, and I don’t just rely on one source. I double and triple check.

SM: Are your subjects, who are sometimes politicians or public figures, helpful to that objective?

JT: Most of the politicians I have dealt with have been very helpful!

SM: Is that true?

JT: Yes – but I don’t deal with everybody. I don’t deal with every member of Congress. But most of the people I’ve dealt with, yes. For example, Congressman Earl Blumenauer of Oregon had a great respect for Paul Simon, whose book Tapped Out was the basis for my films. Congressman Ed Markey, who was elected to Senate last week, was always very supportive and a good man. Senator Dick Durbin of Illinois. I don’t think the Water For the Poor Act would have even seen the light of day without former Senate Majority Leader [2005] Bill Frist, who is a doctor and understood the issues at hand. He had the ear of President Bush at the time [of the Act]. I interviewed former Senator Frist, Congressman Blumenauer, Senator Durbin, and the wife of the late Senator Paul Simon, Patti Simon, for my Water for the World Act video.

SM: These guys work with you, but aren’t blasé or apathetic to the issues when you speak with them for the sake of politics?

JT: Yes, they do. We may not always agree on the issues. I remember having a lot of meetings with Senator Simon and it was remarkable how we agreed on everything from literacy to the death penalty. We had a lot of common interests, but that doesn’t happen often.

SM: What sort of crew size do you work with to get these documentaries made? Certainly big groups can’t be around during these interviews. And do politics ever become an issue when you hire lighting designers, camera people, etc?

JT: Politics rarely come up. I always hire local crews wherever I’m filming, whether it be in China or Africa or India. I was burnt once really badly taking an American crew to Moscow and I’ll never do it again. Most places you go, there’s someone who speaks English and sometimes more than one, which has never been an issue. Again, the issues [in the films] transcend ideologies, so they’ve never been issues, either. Also, I have a technique that I use, so I show my cameramen or camerawomen my prior films, they see how I want to approach the shooting style and the lighting. They see if I want to do Cinema Verite or something. And I have had excellent, just excellent, camera crews in certain places. Usually I like guerilla-type filmmaking where I just have a cameraman, a sound engineer, perhaps another person, and myself.

SM: Are you in every location yourself? Do you ever have to have a second unit for less accessible places?

JT: No, no. I do all my own interviews – any interview you’ll ever see in my films, I have done them all with one small exception: in my Dirty Little Secret documentary about the sexual abuse of young girls, a female psychologist asked most of the questions.

SM: You once had a seventeen-hour interview [with Richard ‘The Iceman’ Kuklinski.] Have you ever had an interview of a comparable length or difficulty?

JT: No, I’ve never had anything nearly as long as that. But I have had some fascinating interviews. I had one with [the late] Georgi Arbatov for my Cold War film [The Cold War and Beyond, 2002.] He was an advisor to Soviet leaders during the Cold War and we spoke for five hours. It was so incredible. I went in with this list of questions I had for him, and I just put the list aside and sat and talked with him about things I’d always wanted to know. These are questions that every American who grew up during that era would be fascinated to know. Like, did the Soviet Union really infiltrate the U.S. State Department? And he responded, “Yes, we did!” He was charming and we just got along great…

SM: Do you hold friendships with subjects like Arbatov? This guy is telling you he infiltrated the American government but you’re still able to maintain a relationship with him?

JT: Oh, yeah, absolutely! We got along really great. I went back to Moscow when I was doing Running Dry and I went into his office, and he just came up to me and wrapped his arms around me in a hug! He gave me a book, actually, and signed it. He was intellectual and was able to talk about the changes that happened between the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation, both the good and the bad. It was very candid conversation, even though it was not on camera and he has sadly since passed away.

SM: You directed all the films you have mentioned so far. Have you produced any documentaries or films that someone else has directed or written, or do you take the reins of each project?

JT: Up to this point, the films have always been mine.

SM: That seems truly rare in a three-decade career as a filmmaker.

JT: Well, when I was doing environmental planning work in Seattle, I would occasionally produce a film for local television. I made a film called A Tale of Two Cities, which I dreamt up! I mean, I had this dream, and I woke up and had this idea for the film! Since then, that’s happened to me a few times, and I wake up thinking, “That’s one hell of an idea.” In this particular case, it was a film that compared Los Angeles to Seattle, or rather the whole Puget Sound area. The question was whether or not Puget Sound was making the same kinds of mistakes California did. I took the idea to the local television station, a CBS affiliate called Kiro-TV, and they decided to do it as an hour-long documentary. I had great help from USC in shooting around Los Angeles, actually. That won a New York Film Critics [Circle] award, so after that, I made a follow-up film, a two-parter. This one was broadcast by KINGTV, Seattle’s NBC affiliate, and the Seattle PBS station and another in Tacoma. It was called Region At The Crossroad, and I published a magazine along with it. I think both films, taken together, had a real effect on people’s concepts of growth management and environmental planning. In fact, I’ve had many people years later acknowledge the project’s long-term, positive impact on growth management planning policies in the Puget Sound Region.

SM: After all these years working, does your filmmaking style continue to change?

JT: Oh, absolutely. I never took a filmmaking class, so you pick up whatever you can through osmosis. The years tell me what I can and cannot do [as a filmmaker.]

SM: Who in the arts do you, as a filmmaker, draw the most inspiration from?

JT: You know, I don’t watch many documentaries. I will rarely look at a documentary because I don’t want to be influenced by someone else’s approach and because I kind of want to have my own thoughts on the subjects. But if the movie is so relevant, like Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004)…I love movies, and I enjoy Michael Moore’s work. I don’t consider his films documentaries, really, though the Academy and his peers do. I don’t fault them for that, either, and I certainly don’t have any problems with him winning Academy Awards.

SM: No matter his films’ genre, he’s clearly a gifted filmmaker…

JT: Oh, totally, and I love his sensibilities. I love his sense of humor and I think he’s great, so I watch his movies. I see a lot of other movies and go to the theater all the time.

SM: Have you seen fiction films that are good conduits for the social issues that your work(s) address?

JT: Well, I just saw The East (2013, Batmanglij,) which I thought was a really cool movie. Its sensibility was just great. And this story of the writer and star [Brit Marling] who has this sort of experience and then gets to act in a film on it is every actor’s dream. But I read some critical reviews that were not as a complimentary, and I want to know what movie those people saw.

SM: I think audiences in general, and especially American audiences, are turned off by films that have social or political issues at the forefront of the stories. I think people believe those films or their subject matters will be difficult to digest.

JT: The big challenge when [a filmmaker] does that refers back to that old statement: take an issue and wrap it in candy. Or the other one: if you want to send people a message, send it by Western Union *laughs*. In my work, I take an issue and wrap it in candy, and I think The East did that very effectively. Occasionally, other films manage to do it well, like George Clooney’s The Ides of March (2011). I think Clooney does that quite often [see: Good Night, and Good Luck (2006)] and I really admire him, too. It’s a big challenge to take an issue and make it palatable. Some films have managed to accomplish that.

SM: Like All The President’s Men (1976, Pakula)?

JT: I just love that movie – it’s one of my favorites.

SM: If fiction can be an active medium for social issue filmmaking, why did you stop making fiction films so early in your career?

JT: I never actually made fiction films. I executive produced a film – for which I found the story – called A Deadly Business (1986, Korty). The central focus of that film, which became a CBS Dramatic Special, was the mafia’s involvement in the toxic waste industry across the industrial Northeast, or more specifically, in New Jersey and New York. The difference [between a documentary and fiction] is that, in a TV movie, you’ve got to take dramatic license. That just goes with the territory, even if you’re doing a “true story.” Hopefully not a whole lot, but normally, you must, and that’s just a part of the art form: it has to entertain.

SM: Other than the subjects you have already dealt with in your work – water, the Cold War, the damage human beings incur on the planet – what others issues do you want or plan to discuss in upcoming projects?

JT: Political ideology and how it is screwing everything up. The fact that decision-makers have less power now than they have ever had because of the various groups for every thing. The presence of social media has changed people in power in a major way – I mean, look at the Arab Spring! The presence of the Tea Party and other splinter groups has truly affected power, in general, in Congress and in the Presidency. It’s just very difficult to get anything done. But the way to [make those films] is to get very interesting people on camera and interview them. And it’s worked for my Running Dry films.

Great interview. Jim Thebaut’s films on water are informative and very relavant. He is doing a great job addressing issues that the public or politicians are not ready to address, but he can do it through film and it works. In general, it is much easier to learn through viewing a film then it is through reading an article or going to a movie.

LikeLike

Jim is very passionate about the topics of his films. Hopefully he can get his message about water across before it becomes more catastrophic. The comments about politics, I believe express the views of most people, hopefully the people in power understand this before it is too late. Keep up the good work Jim.

LikeLike

NEVER before has Jim Thebaut’s work been so relevant. Drought is in the air — and in the news finally, but it was on Thebaut’s radar a decade or more ago with his films about water and “The American Southwest: Are We Running Dry?”

LikeLike