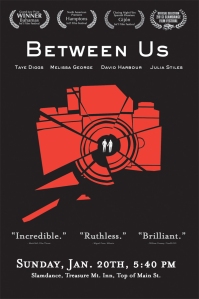

Between Us is the newest film from Slamdance co-founder and director Dan Mirvish, with an adapted script by Mirvish and Joe Hortua from Hortua’s play of the same name. The film stars Julia Stiles, Taye Diggs, Melissa George, and David Harbour as two couples, respectively, whose marriages buckle at separate times in the course of their four-way friendship. A darkly funny marriage drama from award-winner Mirvish (Open House), Between Us fits fairly between its two most significant relatives, Mike Nichols’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1964) and Roman Polanski’s recent Carnage (2010), in both tone and quality. Whiplash is unavoidable between scenes set in New York and the American Midwest, where the couples go from loud bickering to passive-aggressive joking at the drop of a hat.

Though reasonably consistent, Mirvish’s direction sometimes jars with unnecessarily explosive revelations or, alternately, sweet-natured mutterings on the nature of married life. But contrasts here are intentional, and any shock has been calibrated to perfectly destabilize these once-loving marriages. Like its related films, Mirvish’s elicits from its central quartet sharply focused and, in the case of Stiles and Harbour, career-best performances. As Grace, Stiles abandons her lingering teen-lover image for a vindictive, emotionally shattered character unlike her roles in any recent drama; matching her in alternate nastiness and appeal is David Harbour, who originated the role of Joel in an Off-Broadway performance and claims the role as his most complex ever in film. As Mirvish’s highest-profile feature to date, Between Us is destined to find a loving if niche audience, especially for fans who wish to the principle actors’ art-house resumes grow. Further, high profile awards should not be considered out of the question for the hugely popular Stiles.

*****

Mike S. Ryan is an award-winning multihyphenate, best known as an independent film producer and commentator. Mr. Ryan has produced works by directors Todd Solondz, Clark Gregg, and Kelly Reichardt to significant acclaim. Recently, he took a producer credit on the domestic drama Between Us, which will be available on Video-on-Demand via Monterey Media on July 30 as well as on successive festival and online platforms (see above.) Mr. Ryan spoke with Sean Malin of CineMalin: Film Commentary over e-mail to discuss his work on Between Us, what characterizes a “Mike S. Ryan” film, and why making a venison stew for Nebraskan farmers is sometimes necessary for a good producer. This interview has been edited and compressed from text for publication.

Sean Malin: Dan Mirvish, the director and co-writer of Between Us, told me that your mother saw Joe Hortua’s original play at the Manhattan Theatre Club. Was that the first you had heard about Between Us?

Mike Ryan: Yes. I often go to Manhattan Theatre Club plays with my mother.

SM: At the time, did your mother’s description of it entice you to make what is now the film? Or did you come to the project as a producer by sheer happenstance?

MR: It wasn’t until Dan told me about adapting the play that it clicked for me.

SM: How long did it take for the film to go from being “something you’re working on” in a vague sense to something concrete?

MR: We were casting for over two years I think. We had Michael C. Hall attached for a while, and then tried to raise two million dollars, and the whole thing dragged on between money hang-ups and cast shifts.

SM: In getting an adaptation of a play to the screen, is it necessary to be familiar with the source material? Some producers work with total familiarity and affection for the plays or books from which films are made, while others are dropped in cold.

MR: In the end, it’s all about the script for me: does it work, and is it something that I want to see brought into the world? In this case, the intent of both the play and script was the same, and the complex characters and setting transposed well (to film.)

SM: Can you describe your activity on-set? How actively “around” were you during the making of the film?

MR: I was on set for all of the shooting. Sometimes, I even first A.D. my films, but I was behind the monitor with the director confirming for him if we were indeed ready to move on or if we needed another take, and often making comments to him about the performances.

SM: You worked with three other producers to get Between Us made. What skill or talent of yours was the most indispensable to this particular project?

MR: I brought all of the money to the project and was the only producer that was there full time during shooting. Hans (Ritter), who lives in Los Angeles where we shot, was very hands on in pre-production. Producing duties were primarily shared by me and Hans.

SM: Dan also mentioned to methat Dana Altman made venison stew for some farmers in Nebraska. Were those types of acts all in a day’s work on this project? Or is that going above and beyond the necessary call of duty for the sake of a good story?

MR: That was for the second unit shooting in Omaha, Nebraska. In this (type of) case, when you have very little money, you always need to get creative.

SM: Between Us makes the prospect of marriage or the feelings in an ongoing marriage seem extremely, laughably painful. Without the outright slapstick of something like Polanski’s 2009 film Carnage, does Between Us suffer at all from being a “tough sell” to the audiences that might normally enjoy an independent, play-adapted drama?

MR: Yes. Like most of my films, this is serious drama, which is not for everyone. These days, people seem to want typical Hollywood escapism from their ‘indie’ films, so that makes it tough indeed to find the mass audience.

SM: How much of your personality, tastes, or feelings ended up in what finally appeared onscreen?

MR: The two things here that are consistent with most of my films are intense, powerful, Realist-based performances from actors, and the theme of how money can alter or change one’s life.

SM: Are you completely separate of any of the subject matter?

MR: I only work on films that I feel are saying something important about what it means to be alive today.

SM: Do you classify yourself as a “filmmaker?” You’ve tried your hand at several titles – you’ve produced and executive produced, you’ve appeared in films, you’ve worked on crew. What is your primary objective now in the industry?

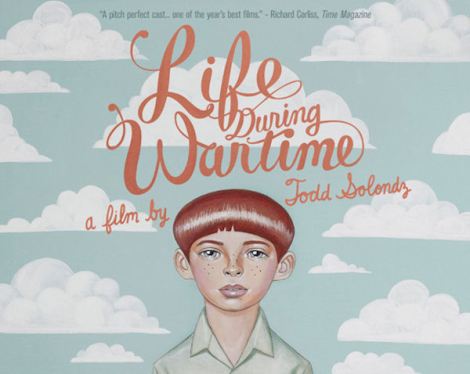

MR: Yes, I am a filmmaker; I work through the director, but I am making the films I want to be seen on screen. The credit title often varies for a couple of reasons. Sometimes, as was the case on Life During Wartime (Solondz, ’10), the financier decides who gets what credit(s). Sometimes, even though I develop and get a film financed, as with Meek’s Cutoff (Reichardt, ’09), if I am not present during shooting, the producers who are present get the ‘P’…It varies for each film. I worked as location manager for ten years before I produced Palindromes (Solondz, ’05) because an earlier film I produced had bankrupted me. But since recovering from debt in 2002, I’ve been full-time producing, which means sometimes writing my own scripts, hiring writers to adapt books I option, hiring directors or just coming on board a writer-director’s project to help cast it, finance it, and make it.

SM: As a producer, you tend to favor the work of the complex auteur: Alverson, Reichardt, Solondz. The idea of a filmmaker as the author of his or her work is a big subject of debate – do you believe in auteur theory? Or is it a total illusion?

MR: I think for some reason people don’t understand the definition of the auteur theory. There is nothing to disagree with, nothing is up for debate, except someone’s lack of understanding of the theory. People think the auteur theory means that a film’s ONLY author is the director. Mostly, screenwriters have spread this confusion about the theory. The point of auteur theory is that a director can express his or her own themes through other peoples material, and that over the course of a body of work, we can discern common themes through one directors work despite there being multiple screenwriters. Auteurist films are not the same as personal films: you can have a personal film and it may not be an auterist film. Sometimes a personal film is the result of a impersonal director translating a personal script to the screen. There are also some directors who write their own material and do so over a few films, and they are still not Auterists. Just because one directs one’s own script doesn’t make one an auteur director. There are several directors whose work keeps showing an expression of certain themes. Those themes can be expressed through their own scripts or through others’.

Todd Solondz writes his own scripts but Kelly Reichardt does not – they are both auteurs. Rick Alverson (The Comedy, New Jerusalem) collaborates with other writers, but all of his films are expressly of his point-of-view. The fact that he collaborates with writers and actors to achieve his vision doesn’t mean he’s not an auteur. The key component is originality: are they expressing a specific and unique point of view?

SM: Do you have filmmakers or performers that you actively seek out to work with? Or do you have directors/writers that you intend to seek for projects?

MR: I sought out Bela Tarr because I was a fan. There are actors that I love who I always look for material that they may want…

SM: You’ve also worked on films that I love but consider demented: The Comedy, Choke, Fay Grim, Palindromes. In Australia, I published a piece on The Comedy for the Sydney Film Festival, where the entire audience was divided in two Cannes-like groups: the abrasive booers and the raucous clappers. What is your attraction to the grotesque behavior and characters in these films?

MR: My films seek to face and respond to the world, and unfortunately, the world is often cruel, unfair, and ugly. The Comedy is a horror film but is also a type of documentary. You may not like that world or those characters but that is the world that exists in Brooklyn today. The Comedy I always saw as an update on American Psycho, hipsters are the new yuppies, irony is their weapon, money and privilege are the bullets. Palindromes was Todd’s heartfelt reaction to 9/11 and the concept of relativism. Osama Bin Laden thought he was doing good by attacking the Evil Empire. The Americans thought they were doing good by illegally invading a country that had nothing to do with 9/11 and killing thousands of innocent Iraqis. The two sides of that coin depict the cruel duality of reality…

As for people who boo The Comedy, we had them at Sundance (Film Festival) too, in part because viewers at Sundance are not educated filmgoers. We had no such reaction at Rotterdam (International Film Festival) where viewers know that a depiction of bad behavior doesn’t mean the film endorses that behavior. The Comedy is a critique of a certain type of person. It uses Brechtian distancing devices to activate the audience. Some viewers who are used to being told what to feel by standard films feel betrayed when they are asked to think for themselves, and react in a way that is unusual for most films.

SM: These are works that are extremely difficult and queasy. They all have messages that come across only after the presence of discomfort and deep sadness. Do you see your career moving further towards projects of this intensity, or away from them? Do you ever say, “Okay, the next project will be softer or sweeter or more transparent?”

MR: I am only really interested in making films that are honest about the world, that are expressions of a personal reaction to the world, and hopefully, that seek to express themselves in ways that stretch film grammar. I think drama that shows people struggling to deal with the world in an honest way is inspiring and positive. Films that only try to escape reality (95 percent of most films) by creating false optimism, perpetuating false dreams or romantic, lazy outlooks on life are totally depressing.

SM: After producing independent productions of this nature, at what point can we start to classify the “Mike S. Ryan” sensibility? Is it too early or are we already there? And how can we, the audience or the press or the critics, discern it?

MR: I think all of my films show a certain sensibility and tendency to embrace difficult material, and that many of the films display a unique embrace of personal, non-traditional film grammar. I don’t like films that are overly plotted; I like slow, lyrical films that seek to express a sense of place and do so through that aforementioned grammar.

Pingback: Dan Mirvish: Hollywood Director Apologizes for Weiner Press Conference | Political Ration·