Paolo Marinou-Blanco is an award-winning screenwriter and filmmaker. His first feature, Goodnight Irene, was released in Europe in 2008 to significant international acclaim. In 2013, he and Maryam Keshavarz were awarded a joint grant from the San Francisco Film Society’s Kenneth Rainin Foundation for Screenwriting on their upcoming feature, The Last Harem. Additionally, Mr. Marinou-Blanco and Ms. Keshavarz are dual recipients of the 2013 SFFS Hearst Grant for Screenwriting. Mr. Marinou-Blanco spoke with Sean Malin of CineMalin: Film Commentary from Portugal to discuss the serendipity of Halloween parties, the power of Franz Kafka, and how The Last Harem is shaping up. This interview has been transcribed, edited, and compressed from visual and audio recordings for publication.

Sean Malin: Your career has taken you from country to country. Isn’t that a bit dislocating?

Paolo Marinou-Blanco: Well, I’ve always traveled like this since I was a child. My dad’s job made it so that we had to move countries every two to four years. He was a general manager for airlines. It was kind of like Toto the Hero (Van Dormael, 1991) – what Daddy did was wear a suit and tie, then he hid behind a door all day and came back in at the end of the day. So I love to travel; I look for it, actually. Any notion of change for me is positive. I get excited being lost in some town that no one else would normally want to go to. Just having to go somewhere that I might hate and finding whatever I’m looking for is always great.

SM: I share that feeling with you, but I have trouble doing any concrete work as I travel, especially when I reach a town or someplace that I hate. Yet you’ve made films and written scripts during your travels over the last decade. I can’t really imagine you sitting down in some office, typing away for hours on end.

PMB: *Laughs* But don’t you know that’s exactly what I do?

SM: Yes – I just cannot imagine how that works for someone of your nature. It certainly does not for me.

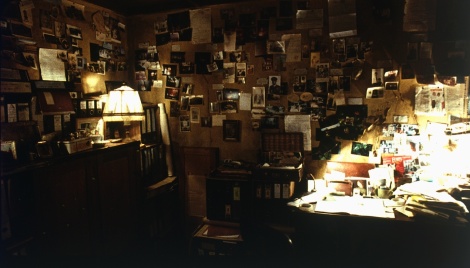

PMB: I see what you mean. One of the great advantages of screenwriting is that you can take it with you, so writing in an office and traveling are not mutually exclusive. You can find yourself with a sense of novelty and excitement, even if it is imagined, while you are chained to a computer for eight hours, so long as it is somewhere different than where you are normally chained. In a way, [writing] is quite easy to reconcile. It is directing that’s tricky.

SM: When you work on a project in a certain location – say, Portugal, where you are now – do elements of your surroundings seep into the projects themselves?

PMB: No, not really. However: environments certainly impact on the free flow of ideas or how constrained I feel in some ways. But no, not in any concrete sense.

SM: What are some of these places where you’ve felt the flow of your ideas constrained by your environment?

PMB: There were certain locations in New York City that I just could not work. Somehow, it just felt horribly claustrophobic, closed in…certain places in London, where I lived for about eight years. Oh god! Places in Northern England, forget about it. There were definitely some places there where I could literally do nothing.

SM: With all this travel, when and where did you and Maryam Keshavarz meet?

PMB: We were both doing a Master of Fine Arts program at NYU [Tisch School of the Arts.] She was two years below me, so we only knew each other vaguely. After NYU, I moved to Portugal in 2003, and began working in Portugal and Brazil for a number of years. I moved back to the U.S. in ’09 and met Maryam again at a Halloween party.

SM: When you arrived in 2009, Ms. Keshavarz must have been at work on Circumstance. Did you start collaborating on something immediately, or was there a gap as her debut film took off?

PMB: We actually met in 2010, and she was finishing up post-production. This was before Sundance [Film Festival 2011] and she was still in sound work. At the time, I had been hired to work on a script called Brass Monkey that was in negotiations to be – and then was – sold to Paramount Pictures. At the same time, I was also hired to work on a screenplay produced by Michael London, whose work on Sideways and Milk, amongst others, attracted me to the job. So I had gotten a foothold already as a professional screenwriter in the U.S. by the time I saw Maryam. But our collaboration started quite organically. The script is based on research she was doing for a Ph.D. and she had had a nine or ten page treatment that contained the germs for the characters. She said, “Take a look at it and tell me what you think.” I told her I thought it was good but that it could be made even better. She immediately clocked on to the fact that we would complement each other quite well as writers; so she asked me if I wanted to work on this [project], and we shook hands. We started developing it as something for television – we actually still have a Bible for the characters, an enormous, wealthy group – but we decided it would actually work well as a feature.

SM: How does one make that distinction in a project that uses a Bible of character traits? At what point did you realize that The Last Harem would work best as a feature film?

PMB: It’s actually not a matter of better or worse; we both still feel that it would make an excellent TV series. We feel that the panoply of characters, the period setting, and the themes of the 19th century are both contemporary and suitable for our epoch. That being said, a feature film is a more gentle introduction to this world. We plunged so deeply into this project, coming up with plot line after plot line and character after character, that, in the end, everything started to sound so rich that such an introduction seemed appropriate [to the material.]

SM: Your choice of the word “Bible” speaks to a growing theme in American media. The idea of a tome being the basis for a program or film is becoming more and more prolific, with the major examples being HBO’s series Game of Thrones and History Channel’s The Bible. If you and Maryam had been preparing a project of this scale a few years before these epics had found success, The Last Harem might not have even been saleable…

PMB: I agree one hundred percent. This is absolutely its time. There is an increased awareness that period pieces can also be quite contemporary. In film and television, even in theatre, this sort of bridge in time can be made interesting. And we wrote it with this aim in mind: for The Last Harem to reach a world that is more ready for it.

SM: Are there certain projects in theatre, film or television that you look at for validation or inspiration?

PMB: I am very much influenced by French theatre. From Moliere to Jean Racine, to Jean Cocteau, they have always included things where history reflects our own times back to ourselves. But I do confess that few contemporary playwrights come to mind.

SM: You forgot to mention Marcel Duchamp, even though you made a short film about him. He seems to be operating in his films and visual art in a similar way, though perhaps in a more fantastical realm. Does his influence affect you?

PMB: Well yes and no: in The Last Harem, we have yet to exit the realm of naturalism. But the reality is itself so crazy at times that the line between what actually happens and the Surreal is very fine. So in a way, just by virtue of what is really happening [in the script], we are dealing with the world of the Surreal. The conditions and rituals that some of these women had to endure…Things that were forbidden or not forbidden, the harems themselves are almost on the lines of Bunuel or Cocteau in terms of this hyper-real surreality. I don’t mean to sound like a complete pretentious wanker…

SM: I’m the wanker – I asked the question in the first place. Speaking of questions, how are you and Maryam going to divide responsibilities on the film?

PMB: Maryam will direct and we are co-writing. I will produce with her as well.

SM: You mentioned earlier that your work in the U.S. had gotten you a foothold in the industry. Does that mean you are also moving towards another feature as a writer-director?

PMB: I’m working on a dark political comedy set in Brazil, which I’ll shoot in the near future. As I already have a strong foothold as a professional writer-director in Portugal, I have both a Brazilian and a Portuguese producer for the project already; and I also recently won a spot at the prestigious Mediterranean Film Institute’s screenwriting lab in Greece. It’s got the Olympics as background. Two facts set me on the story: One is that the Brazilian government is currently evicting people from the poor neighborhoods of Rio de Janeiro in order to make room for Olympic buildings. The other is that golf is becoming an Olympic sport.

SM: Those are facts in our current world or in your world? Talk about “hyper-real surreality.”

PMB: *laughs* Those are actually happening. Golf becoming an Olympic sport is nothing if not comical to me. While Rio de Janeiro is being turned upside down, gearing up to host the Olympic Games, we dive into a dark comedy about Candido, a working class man who tries to save his neighborhood from corrupt real estate developers and Olympic Committee officials…through murder. But his plan has one tragic flaw: he’s no killer. As this sweet man doesn’t have the heart to murder the rich, corrupt entrepreneurs, he kidnaps them instead, and imprisons them in an abandoned, decaying resort hotel by the seaside.

SM: *Laughs* Oh yeah, he sounds like a total sweetheart.

PMB: In a darkly comic and satirical progression, the initial captor becomes the captive: this good-hearted, working-class “angel of vengeance” finds himself in the same cycle of exploitation he was trying to avoid. He becomes a caretaker for the kidnapped rich, spending all of the little money he earns from the “contracts” on looking after them, as well as fulfilling their absurd demands – because he’s such a gentle-hearted guy! He’s such a sweetheart that, even when he was in the elite military unit, he worked in the laundry service. He couldn’t kill anyone.

SM: It seems pretty real already. Do you have a title?

PMB: So far, “Carioca Olympics.”

SM: And will this film unite the themes that you’ve discussed as influences on you and The Last Harem?

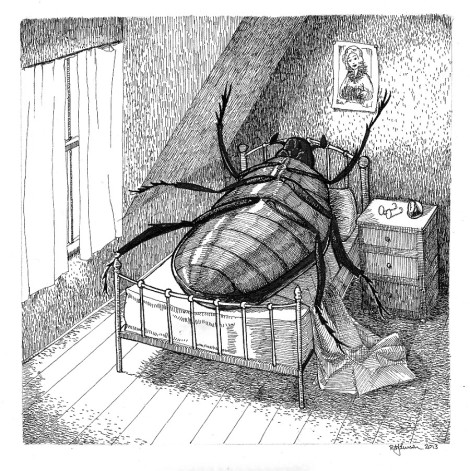

PMB: For me, the best kinds of projects are the ones that have a dramatic tangent to reality. A simple example would be in the work of Kafka. Take one of his most famous stories, “Metamorphosis” – it’s a truly insane situation, the one that Gregor Samsa is in, and yet, as the story opens, he is noticing a painting on the wall and how bizarre it is that the woman in the painting is wearing hand-mufflers when the weather behind her seems so warm. This is truly Surreal: to have been transformed into an insect but to be focusing on, you know, the incongruent aspects of some painting in front of you. It is the same thing with this screenplay and the facts. If you have a solid understanding of one fact’s arc or the components that constitute the world of the film, only then can you, as a filmmaker, begin to distort these parameters to dramatic effect. I find that these permutations of reality actually help me, in a way.

Editor’s Thanks: Still images and ‘Carioca Olympics’ abridged synopsis provided graciously by Paolo Marinou-Blanco.

Pingback: Interview with Maryam Keshavarz | CineMalin: Film Commentary and Criticism·