What: Film Review

Directed by: Stephen Silha and Eric Slade

Co-directed and Edited by: Dawn Logsdon

Featuring: James Broughton, Jack Foley, Neeli Cherkovski, George Kuchar, Armistead Maupin, Joel Singer, Pauline Kael, Suzanna Hart, Anna Halprin, Lawrence Ferlinghetti

Running Time (in min.): 82 minutes

Language: English

Rating: Not Rated

Official Selection of the 2013 SXSW Film Festival

****

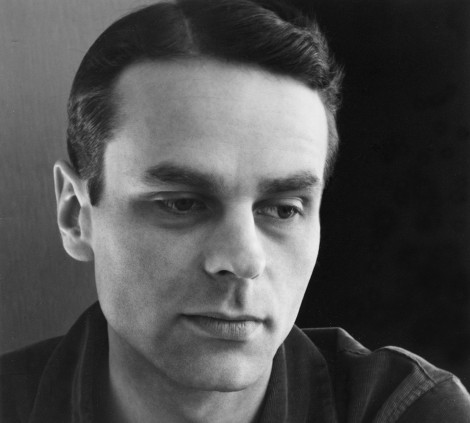

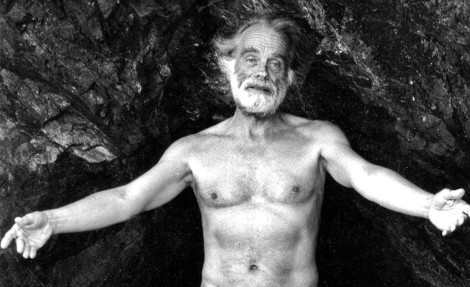

The largest pleasure of the aptly-named Big Joy: The Adventures of James Broughton is the sight of the avant-gardist, poet and general artiste of the title nuzzling noses with his late-in-life lover, Joel Singer. To that point in his career, it seemed that the antic, slab-jawed Broughton was in combat with his own nature – queer, but sexually repressed; eccentric, but classically Romantic. Yet in the face of a long-standing marriage and the trials of heternormative home life, he pursued a relationship with Singer (who also executive produced the film), and made his most emotive and becalmed films. Ah, but if all art was filled with so much warmth, we’d get heat stroke.

Wisely, directors Stephen Silha and Eric Slade, and co-director and editor Dawn Logsdon, avoid the fatal trap that so many biographical docs suffer: trying to imitate through technique an inimitable artistic personality. It would have been impossible in this case. As a pioneering force in the American experimental cinema, a poet and writer who preceded the explosion of Beat culture in San Francisco, and friend to such notables as Allen Ginsberg, Stan Brakhage, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and the late George Kuchar (who is interviewed in the film, perhaps for the final time onscreen), Broughton was the kind of man destined to be the subject of a flick about his life.

That is to say, he was idiosyncratic, complicated, and inappropriately valued – read: ignored, mostly – by cultural historians and the public alike. As The Independent wrote in its 1999 obituary: “he never was fashionable…” Such is the life of most avant-garde artists, of course, but Big Joy attends so respectfully to its subject’s work that, by the time the film ends, there is no doubt that Broughton was as important as he was gifted.

After a childhood in the mid-Californian town of Modesto, he made his way in the early 1940s to the Bay Area, where he would spend nearly fifty years making films, writing poems, publishing books, and starting a family. By 1946, he and Sidney Peterson had co-created The Potted Psalm, considered by many the first experimental film ever made in San Francisco; a year later, Centaur Press put out his first book. Both projects are chaotic, Surreal, lyrical and vaguely sinister, suggesting that Broughton was as much a prankster as he was a poet.

That art reflected life so consistently in this case should come as no surprise to those versed in historical icons. Silha, Slade, and Logsdon rightly refuse to sugarcoat the great mess that Broughton, who was otherwise charming enough to earn several cheery monikers, made of his own life. His film work, for example, was unabashedly queer – groundbreaking in its use of sexuality in such films as The Pleasure Garden and The Bed, perhaps, but deadly to the finances and popularity of anyone trying to feed a family. By 1947, he had entered and exited a relationship with the American critic Pauline Kael, and they’d borne a child together. He had another two with his wife Suzanna Hart, only to begin exhibiting his films and reading his poems on tours around the world. The effect of this is succinctly put by his and Hart’s son, Orion: “it’s not that he was a bad father…he just wasn’t there.”

Hart’s and Orion’s interviews for Big Joy reveal such deep sadness and abandonment that one can hardly believe the source of such feelings was alternately known as, “Sunny Jim.” For those familiar with Terry Zwigoff’s magnificent Crumb (1994), segments with Broughton’s son recall Zwigoff’s talks with R. Crumb’s brother, Charles (though not quite as macabre.)

But Logsdon and co-editor Kyung Lee make the inspired choice to juxtapose Orion’s scenes with those of the artist’s friends and, especially, his soulmate. After leaving his wife for Singer, one of his students, the inner struggles that characterized Broughton’s early life and work seemed to cease, and his final years became rich with creativity, respect, and overwhelming love. In his last twenty years, he became a renowned professor in San Francisco, published a memoir, and received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Film Institute. You win some, you lose some, as they say.

Appropriately, affection bursts through the screen in the film’s last act, giving the constant montage of interviews with Singer, footage from the films he directed with Broughton, and a sweet voiceover performed by Davey Havok a rare vitality often missing in American documentary. Silha, Slade, Logsdon, and Lee generate the sort of emotional crescendo found more often in investigative documentaries, no surprise given their suggestion in press notes that the work of James Marsh, Errol Morris, and D.A. Pennebaker served as personal inspirations for Big Joy. Yet theirs is an enamored portrait of their subject as well as a critical one.

That this particular documentary is neither as adventurous nor as experimental as Broughton’s work is understandable in this light – the filmmakers are aiming more for memoir than poetic portrait, which may have supported more formal ambitions. Instead, they work chronologically and focus equally on his historic achievements as on his personality (a smart tactic: the film has won awards and shown at LGBT festivals around the world.) Big Joy: The Adventures of James Broughton works best as an antidote to the “unfashionability” so frankly articulated in his obit. You will come away knowing that this man was a major queer activist, a predecessor to and participant in several of America’s great cultural movements, and a visionary artist. But you’ll also wonder, perhaps sadly, when the rest of the world will get the same message.

Editor’s Note: Big Joy: The Adventures of James Broughton will screen at the Austin Film Society on August 27, 2014 as part of the Avant-Cinema Series, co-presented by OutSider Film and Arts Festival. Tickets are available for members and guests here.