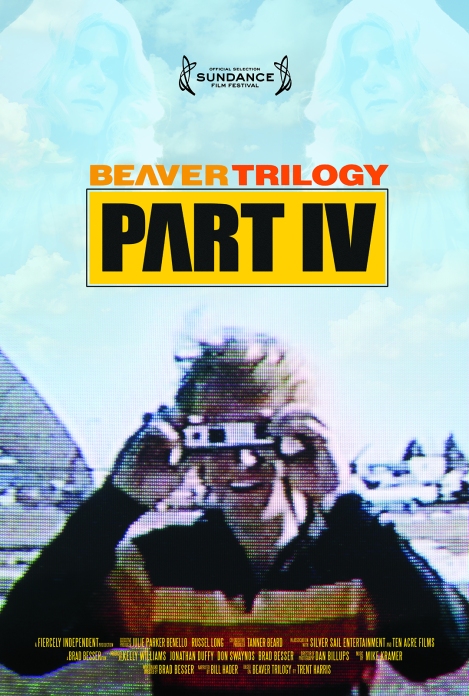

What: Film Review

Directed and Edited by: Brad Besser

Produced by: Brad Besser, Kelly Williams, Jonathan Duffy, Don Swaynos

Featuring: Trent Harris, Richard “Dick” Griffiths a.k.a. “Groovin’ Gary,” Brad Besser

Narrated by: Bill Hader

Language: English

Running Time (in min.): 84 minutes

Rating: Not Yet Rated

Official Selection of the 2015 Sundance Film Festival

****

The pillars of great documentary filmmaking have suffered so much erosion to their reputations from the never-ending whirl of easily palatable, sometimes widely popular, bullshit that even the remotest hint of self-interrogation in new projects can feel like a pump of lifeblood into the genre. Over the last few years, these heaving, desperate heartbeats have come in the form of so-called “hybrid” documentaries like Sarah Polley’s ingenious Stories We Tell (2012) or Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing/The Look of Silence (2012/2015, respectively), both of which are actually just nonfiction films that simulate the fiction process metatextually. And even as exemplary as these films are, they remain consistently mislabeled, misunderstood, and isolated.

I worry, then, for the fate of the aggressively reflexive second film from Brad Besser, which has just had its World Premiere at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival. Besser has challenged himself with a goal as self-obsessed as Synecdoche, New York (2008) without the Kaufman script: the complete dissolution of verisimilitude in a feature-length documentary about the filmmaker Trent Harris’s underground classic, The Beaver Trilogy. The result of Besser’s efforts, Beaver Trilogy Part IV – a title which remains the first and best joke of an unexpectedly riotous work – is bound to inspire many thinkpieces (or at least blog posts) on the nature of nonfiction filmmaking, the documentary gaze, manipulation of on-camera subjects, and the like. What a waste most will be.

That’s not to say that Part IV doesn’t deserve to be the subject of wide critical thought; on the contrary, the film is so intellectually daring in its un-seriousness that it, like Harris’s own work, will quickly begin to make the rounds of variously lauded higher-learning institutions as soon as the festival ends. That fate could be as much boon as curse, as only time will tell. Besser, who edited and produced in addition to serving as director, has his cake and eats it too by subtly shift subjects. What starts as an investigation into the making of Beaver Trilogy, a series of underground short films alternately vérité and staged, allows itself to be taken with Harris himself before returning to the subject of “reality” in the elder filmmaker’s work.

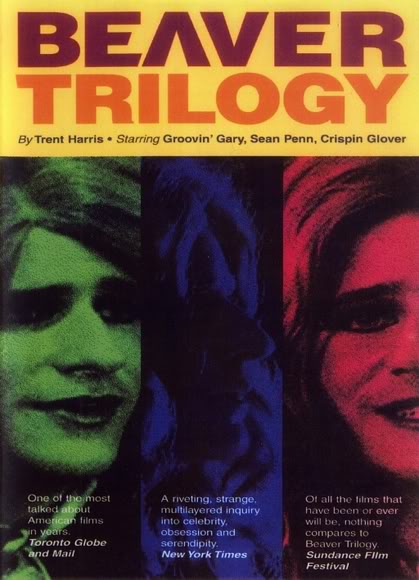

There are some things we prefer to believe we know about these shorts. The first, from 1979, was shot on Harris’s first day with a Super-16mm camera given to him by a Utah news show. Testing in the station’s parking lot, he came upon a compelling stranger who immediately performed impressions of John Wayne, Sylvester Stallone, and Barry Manilow. Harris dubbed him “Groovin’ Gary,” and followed him by request to a high school talent show in Beaver, Utah, where Gary – actually named Richard LaVon Griffiths – performed an outrageous stage number in full drag under the moniker “Olivia Newtown Dawn.”

Amazed by Griffiths’s gall and the beautiful collision of naiveté and courage required to appear on camera in such a capacity in 1979, Harris chose to pursue the story further in his own way. Over the next decade, he wrote and directed two expanded sequels. The first, starring Sean Penn as a character called “Groovin’ Larry,” is rumored to have been shot for $100 and circulated exclusively through self-made bootlegs. The second, the filmmaker’s thesis film at the American Film Institute, was made for near $50,000 and featured Crispin Glover as the even-more-fictitious “The Orkly Kid”. And finally, in 2001, as a set of three, the short films played to huge acclaim at Sundance.

Harris, a cult hero and accomplished educator, visual artist, and filmmaker (above and belowground), places such strong quotation marks around his concept of “reality” so often in his own work that it seems natural to focus a nonfiction film around the man (you can read more of his conception in our upcoming interview with the filmmakers.) As with Harris, Besser is smarter than to let the film settle into a hypocrisy of tropism and documentary tricks, except in his inclusion of unnecessarily expository voiceover by the great actor Bill Hader. Most of the time, Hader’s narration is innocuous and pleasant; but the film is so rich in editorial skill and introspection that even such talents as Hader’s serve as little more here than window-dressing. Otherwise, the film is typified by many grace notes and a facility for storytelling uncommon in nonfiction features of any kind.

The result of Besser’s efforts is that what could have been a talking-head driven historical research project on the trilogy segues quickly to the compelling, game Harris before finally settling on the process of Besser’s own self-inscription into the Beaver Trilogy’s legacy. Part IV acts as testament (and characters in the film, like Griffith’s three sisters and Harris, speak openly of this) to the up-and-coming filmmaker’s own obsession with form and thought, allowing itself to be both personal and lovably scattered. It’s an unusually funny film, too, which helps the somewhat esoteric subjects go down without much hassle. It’s all in the name of questioning reality for Besser, who blurs lines as adroitly as Harris himself while paying homage to such questing meta-documentary predecessors as Joris Ivens and Werner Herzog. These directors are, of course, inimitable, and as inappropriately labeled in the marketplace as the Polley or Oppenheimer projects above. Nonetheless, with a little bit of luck, one hopes that Besser’s exemplary work here and going forward won’t suffer the same fate.

Pingback: Sundance Interview with Brad Besser and Trent Harris | CineMalin: Film Commentary and Criticism·

Pingback: Interview with Kelly Williams and Don Swaynos | CineMalin: Film Commentary and Criticism·