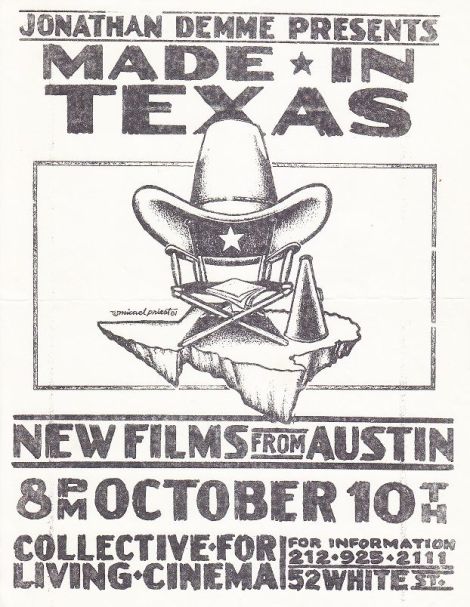

Louis Black is a writer, filmmaker, and media producer best known as the co-founder of the South by Southwest Festival (SXSW), a co-founder of the Austin Film Society, and the editor-in-chief (and co-founder) of The Austin Chronicle. In 1981, he collaborated with Academy Award-winning director Jonathan Demme on the Made in Texas series, a screening of six films produced and made in Austin that premiered to widespread acclaim at the Collective for Living Cinema in New York City. A new restoration of the series was officially selected to screen in the Special Presentations category at the 2015 SXSW Film Festival. Mr. Black supervises the digitization, preservation, and restoration of the series now titled Jonathan Demme Presents: Made in Texas.

To celebrate the Made in Texas screenings at South by Southwest in 2015, Louis Black spoke with Sean Malin of CineMalin: Film Commentary and Criticism about his more than thirty years of collaboration with Mr. Demme, the current state of Austin underground filmmaking, and the many influences that continue to drive his productivity across the media platforms. The editor would like to thank Hallie K. Reiss of the Texas Short Film Archive & Registry for her efforts in arranging the interview. It has since been transcribed, compressed, and edited from audio for publication.

*****

Sean Malin: It does not seem too long ago that you and Jonathan Demme worked together to show the Made in Texas series, but it was a major moment in American film at that time. What made it such a big to-do?

Louis Black: There were a couple of reasons it was such a big cultural event. One was that it celebrated regional cinema made completely in the heartland of Texas, not in New York or Los Angeles. Two, there was the fact that the series was presented by Jonathan Demme, a very hip director at that time. Another thing was that it demonstrated that the punk scene was alive and well outside of New York and Los Angeles. By 1981, this was already clear because bands like the Big Boys were starting to break. In fact, the first time I talked to Jonathan, he had a cassette on his desk of Austin punk and New Wave bands.

SM: Some of these films went pretty big.

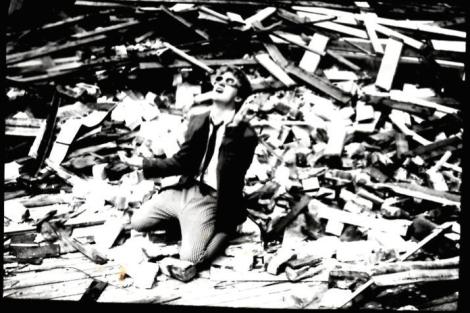

LB: Two of them in particular received a lot of attention: Invasion of the Aluminum People [dir. David Boone] and Speed of Light [dir. Brian Hansen]. People started getting in touch immediately to try to see the films. If not for the fact that films like those were delivered exclusively by film societies at that point, those two could have gone the furthest of the six. It’s not like today where there are viral and online delivery systems for these kinds of films to screen.

As it was, though, the reaction was enormous. Bernardo Bertolucci raved about Speed of Light, Diane Keaton loved them, Carrie Rickey wrote good things about them.

SM: Amy Taubin also wrote about the films on a very public forum for 1981. I remember reading her comments just before seeing this series for the first time at the Austin Film Festival in 2013.

LB: Actually, Amy Taubin has said that Invasion of the Aluminum People was her favorite Super-8 film of the 1980s. At the time, before this became the place where Rick Linklater and Robert Rodriguez were making films, and Mike Judge was moving here, and all the other amazing people that have come up since, you would have bet against any of the decade’s best experimental films being in a series of shorts from Austin, Texas. But there they were.

SM: The fact of Taubin’s even mentioning regionally-made work in the Village Voice was an anomaly at that time. Scholarly and trade criticism were continuing to ignore experimental movies of any kind that were not coming out of the big metropoles. I mean, sometimes you heard about Brakhage, Deren, and Kenneth Anger from Jonas Mekas, but otherwise not. Were you and the filmmakers completely taken aback when people like Rickey and Taubin wrote about them?

LB: I do think it was unprecedented, though that’s not to say that other regional films had not broken out. McLuhan brilliantly said that we tend to think of current media in terms of past media; and if we think that idea through, we realize that art from the present is actually reflective of art from the past. When these kinds of films were being made, you had to go to New York, Los Angeles, Paris, or London to get to them because art doesn’t happen all across the country at the same time. So you find those first and second generations of experimental filmmakers almost all being based in one of those big cities.

To see something like Speed of Light coming out of a place like Texas, no one would have thought of that, myself included. It was just Jonathan saying, “We’ll show these in New York,” to which I responded, “But there’s one you haven’t even seen.” That was, of course, Invasion of the Aluminum People, which along with Speed became the biggest hit.

SM: Here we are talking in 2015 and underground films from Texas are still being made, no doubt. But the question is whether the wider movement is waxing or waning – after the Made in Texas films screen at SXSW, will they be part of an active scene for experimental film?

LB: Experimental film continues to drive mainstream cinema now as it always did. I was there when the films of Godard came out, and he ripped the language of cinema apart. But when you watch those films now, they’re so boring – I find Breathless [1960, aka Á bout du souffle] very boring – because every idea Godard ever had is in a television commercial. Network TV and cable have taken his use of language and made it commonplace. In the later ‘60s, you’ve got Kubrick taking all the techniques that Jordan Belson was using for experimental film and putting them directly into the mainstream.

The transition time from experimental to mainstream is shorter than ever: if someone has a good idea, they put it on YouTube for someone else to find. The language [of filmmaking] is so malleable that it becomes hard to keep up. It’s the same with how children speak, and I’m not saying that to be some old curmudgeon – the same can be said of music or mainstream film. Whenever someone has an innovative idea of any kind, it goes everywhere. Just look at something like Birdman. Innovatively told –

SM: …But the story is pure, classical narrative entertainment. It’s simple and straightforward.

LB: Exactly, and that’s part of why I loved everything about it.

SM: It’s funny you mention that because when I first came into contact with experimental film, I had already seen the visual tropes that had been pioneered by Buñuel and Brakhage and Belson, but never those filmmakers’ films. And then I noticed the same thing when I began to watch the Great American Classics: I recognized every image in The Godfather [1972] before I’d ever seen it, and Lawrence of Arabia [1962], or Casablanca [1942], etc. Now, I see the same thing happening when I encounter Austin underground films at places like Experimental Response Cinema, Mad Stork, AFS – images seem familiar to me before I’ve ever seen the work. And like you, I love that feeling. Are you still interested in seeing that kind of stuff?

LB: Even though I’ve seen more experimental films than most people – I watched chunks of [Andy Warhol’s] Empire [1964] and Chelsea Girls [1966] – I’ve never been that interested in “experimental” film. I’m interested in ALL film.

SM: You didn’t finish those films, though?

LB: *Laughs* Oh, no, no. I watched an hour of Empire and I got the point. I never loved experimental film so much as I loved how experimental film influenced mainstream filmmaking. It’s like poetry – there’s a kind of poetry I’m just not going to read, but when it ripples back into the literature, the language gets completely torn up. In that way, I’ve always been a bit conservative.

SM: I have trouble thinking of you as someone with conservative taste just based on your accomplishments. For instance, you made one of the independent films in the Made for Texas series, not to mention the films you’ve supported as a producer, presenter, or executive.

LB: The film I made [Fair Sisters, 1981] is more of an homage to Jonathan than anything else. There was another in the program that I produced, The Mask of Sarnath [dir. Neil Ruttenberg] that holds up well, but the real strengths of the program were always Invasion; Speed of Light; and Death of a Rock Star [dirs. Tom Huckabee, Will van Overbeek], which I think will get a lot of attention after SXSW for its amazing new score. That film was lost for a while as The Death of Jim Morrison. But I don’t think I’m being modest when I say my short is the worst in the bunch simply because it’s the most traditional.

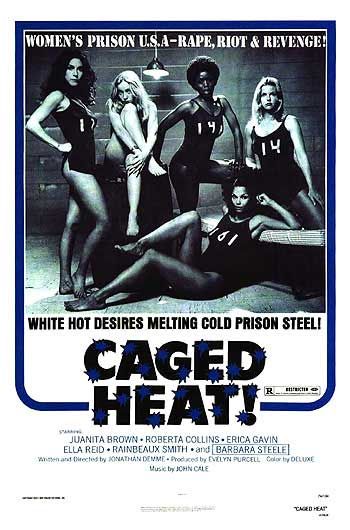

SM: I see what you mean. Still, I know that you made Fair Sisters with an abiding admiration for Mr. Demme’s Caged Heat [1974] and Crazy Mama [1975], and those films were hardly traditional for their time. Like many of the filmmakers you support in Austin and otherwise, like Richard Linklater or John Sayles, he was a maverick and a journeyman in the John Frankenheimer mold.

LB: It’s funny because there was a moment once where I said to [Mr. Demme]: “You know, the reason I fell I love with your films, originally with Caged Heat and again with Crazy Mama, was because of how many women’s roles, ethnic roles, gay couple characters, and completely untraditional families you used for that time.”

SM: Is it true that you brought Mr. Demme to Texas on the basis of seeing those films?

LB: In the seventies, I had begun attending movies through Cinema Texas [at the University of Texas at Austin] and one day, my friend Ed Lowry said, “There’s a movie playing at the drive-in that you really should see.” So we went to see Caged Heat together and by the end of it, I was banging on the roof of the car asking him how he could be so calm about this. For weeks after, that movie was all I could talk about. They screened Crazy Mama at the school soon after that, and I also saw a great rock film called American Hot Wax [1978, dir. Floyd Mutrux] that convinced me to write to Jonathan. Evidently, he got my letter on a very bad day and had an intimate relationship with it for some time. Eventually, though, he came to town, and we became friends.

SM: Even the films that he makes in a more traditional Hollywood style – from Silence of the Lambs [1991] to Philadelphia [1993] to Rachel Getting Married [2008] – break through so many molds that it’s hard to keep track. I can see in those films what attracted him to the Made in Texas series all those years ago. Now, we’re talking more than thirty years since that first screening in New York, and you and Mr. Demme remain close. What’s the tie that binds a relationship like that?

LB: Just as it seems crazy now that we had Speed of Light and Aluminum People in one program, the first film I produced was Margaret Brown’s Be Here to Love Me: A Film About Townes Van Zandt [2004]. I got involved with that project because I love Townes – it wasn’t until long after the film was complete that I realized Margaret was a brilliant filmmaker. She had the kind of luck that almost never happens: her first film was an aesthetic triumph. Jonathan is always looking for this kind of stuff, too. He is literally always seeking out new music, new films, and new, exciting ideas for work. I think all the films in the original series were interesting to him – certainly the filmmakers’ audacity and confidence blew him away. And to me, that was an authentic, appropriate response. Even Rick [Linklater] had seen the films at a screening in Houston at some point and they have influenced him as well.

SM: You’re working with Hallie Reiss of the Texas Short Film Archive & Registry to preserve, restore, and digitize the Made in Texas films into perpetuity. This is a major moment for archiving in Austin while the AFS collections and the Texas Archive of the Moving Image continue to grow. Why did you embark on this project?

LB: It was such a weird, extraordinary evolution. After the screening at Austin Film Festival in 2013 [which we both attended] with Rick, and Jonathan, and Paul Thomas Anderson who all loved it, I started by thinking we could just take care of Speed of Light and Aluminum People. But I realized we might as well present and preserve the whole program, and maybe make some new copies of the original Cinema Texas program notes while we’re at it. What’s still amazing about this process is that for a series like this to be made in Texas was just crazy to me. At the time they were referring to Texas as the “Third Coast,” which I thought was a complete exaggeration. It turned out that I was short-sighted and wrong because what you have here is an incredibly supportive community.

SM: It seems to me, after living here a few years that everyone wants to help everyone else out. Filmmakers have told me they’ll volunteer for their friends if they’ve got the weekend off.

LB: You have scholars, experimental filmmakers, students, animators, and studio filmmakers who all know one another and all work together. Then you’ve got Linklater doing his “Jewels in the Wasteland” series at the Austin Film Society, and people keep turning out for those events. There’s just so much collaboration – of course there are also bad people and some bad blood, like anywhere – but people support each other. That’s why whenever I’m out and I’m introduced to someone new, I invariably say, “Please get in touch with me – I’m very interested in your project!” Sometimes they do and it leads to another movie; and sometimes they don’t and I’m left with the vague memory of a project I can’t wait to hear more about sometime *Laughs*.