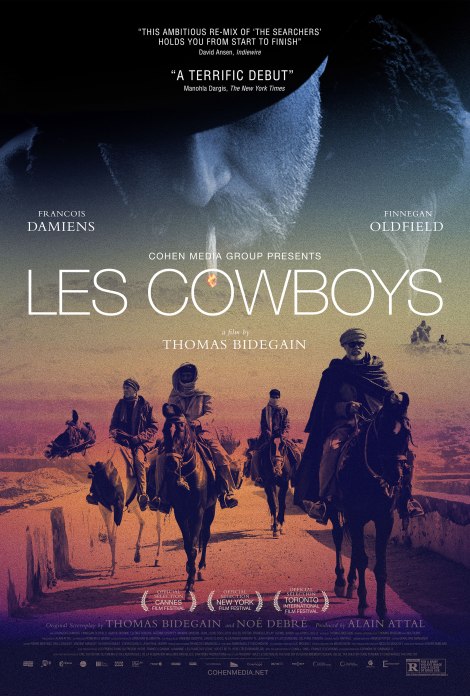

Directed by: Thomas Bidegain

Written by: Thomas Bidegain, Noé Debré

From an Original Idea by: Laurent Abitbol & Thomas Bidegain

Starring: François Damiens, Finnegan Oldfield, Agathe Dronne, Iliana Zabeth, John C. Reilly

Produced by: Alain Attal

Cinematography by: Arnaud Potier

Editing by: Geraldine Mangenot

Music by: Moritz Reich

Official Selection of the Cannes Film Festival 2015

A Cohen Media Group Release, Now Playing

*****

Last month, I wrote about the completist ethic and the desperation we as film lovers share, I suspect, to follow artists along their paths from project-to-project simply for the sake of the following. That piece referred directly to the ever-elusive Terrence Malick, who’s late-career explosion as a producer and filmmaker has birthed an unusually wide range of quality works. But the desperate fascination with him (or Scorsese or the late Abbas Kiarostami) might easily apply to several other contemporary filmmakers; and at least three of them (and the ghost of a legendary actor) surface in a new international co-production called Les Cowboys.

The screenplay and direction are by Thomas Bidegain, whose scripts for A Prophet, Rust and Bone, and Where Do We Go Now? elevated him from decades of B-level French script-doctoring to the lofty airs of the art house. The first two, as directed by Jacques Audiard (they also co-wrote last year’s Palme D’Or winner Dheepan), grounded superb naturalistic performances within sensational genre writing – that is, from inside the boundaries of the crime epic (in the case of Prophet), the romantic drama, and the thriller. These films contain an inherent nostalgia: their décor (which is often post-modern, sparse, and slyly brilliant) aside, they are all throwbacks reminiscent dramatically of the classical eras in both Hollywood and France. Bidegain’s and Audiard’s scripts, these films’ blueprints, are among the best produced in this millennium, and here, Bidegain’s co-producers are the Belgian master directors Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne. Les Cowboys is an auteurist’s wet dream in Pashtun.

So it is more than appropriate that Bidegain chose to marry recognizable (in other words, overdone) classic genre clichés with a somewhat realistic and fact-based, post-9/11 thriller in his feature directorial debut. Named after the film on which Bidegain based his, The Searchers, the genre being replicated is the Western, and more specifically, the epic, heavenly cinema of John Ford. We’ve all got to start somewhere, I suppose.

Setting us in the late 1990s, Bidegain repurposes the Ethan Edwards character originally played by John “Rooster Cogburn” Wayne as one Alain Balland, an Arab-hating family Frenchman played with pent-up hostility by François Damiens. When Balland’s daughter Kelly (Iliana Zabeth, a calming and capable presence) goes missing at a neighborhood party – likely taken up with her suspicious local boyfriend Ahmed – Balland goes apeshit, putting on an outdated black cowboy hat and taking his son, The Kid, with him. As in Ford’s film, nearly a decade goes by without luck, and Balland and his boy part ways. Now grown, Kid, who is brought into adulthood by the actor Finnegan Oldfield with wizened bags of sadness under his eyes, takes up the search for Kelly, in the meantime causing trouble with the ghettoized Arab communities of Central Europe.

Bidegain’s and Noé Debré’s script (the two also collaborated on Bertrand Bonello’s Saint Laurent) takes us nation-hopping, an almost Bourne Identity-like maneuver for reminding the audience of the ongoing continental immigration crisis. The Kid’s intentions are purer than his father’s, grounded more in the discovery of his sister than on an anti-Arab crusade, but he becomes a pawn for the larger forces at play. Iraq War American militarism is represented as one such force by John C. Reilly, whose teeny role is nevertheless profoundly scary (and certainly marketable in the U.S., where the film is being released by Cohen Media Group.) In his scenes with Reilly, Oldfield shines, a desperate and weakened young man against a seemingly wraith-like presence. Les Cowboys concludes without any sense that the phantom of Western imperialism will somehow go away.

If we disregard the imminent (and inevitable) complaint that a film as popular, controversial, and acclaimed as The Searchers was re-made or in any way rebooted, still the question remains of what compelled the writer/director to turn his first film into an homage. The press notes are clear that departing from Ford’s film is intentional: if the laws of the Old West no longer apply, then neither should the aesthetics. I agree: Ford’s was an epochal film that opened up filmmakers and critics alike to the possibilities of conflicted awe-struckness in a way that even Birth of a Nation, which heralded the Ku Klux Klan, could not. But that story has been told in every film school and book on Westerns since the dawn of Ford’s career, and Bidegain’s huge ambition rightfully pulls him further into the present than in the same complicated, un-venerated past that Ford walked through.

The Edwards character, whose hunt for the American Indians that “kidnapped” a niece (played in the film by Natalie Wood), was an unrepentant racist and vagabond with amazingly current orange-haired doppelgangers. Yet Ford’s universe was far from the uncomplicated world of black hats versus white, Americans versus Mexicans, cowboys versus cowards, in which most American southwestern films set themselves. The landscapes of Utah, New Mexico, and Texas ensconced The Searchers in a world without industry, metallic personal mechanisms, and post-modern architecture – they existed in a time before the telling of time. And Wayne, in his crowning performance as Ethan Edwards, inspires repulsion and fear in many conscientious viewers today for his far-gone, abject racial and social hatreds. For reasons like these, scholars like Joseph McBride and Glenn Frankel continue to expand on the legacy of The Searchers and many other Ford-directed films at symposia around the world.

So where is John Ford in all of this? Most prominently, in the presence of the racist Alain, who Damiens invests with a brutal charm and earnestness – the man seems truly to miss his daughter, almost as deeply as he believes she was “kidnapped” and forced into Muslimhood. Damiens has the powerful, sinister baldness of the older Bruce Willis, but he’s an unredemptive character now, much like John Wayne’s Ethan Edwards looks to the modern audience; yet we can forgive Wayne his impropriety, his social impoliteness, and his character’s coldness, because Edwards existed 150 years ago. Balland’s cowboy hat, by contrast, looks insipid, not heroic, and its anachronistic quality is without charm. While Bidegain and Geraldine Mangenot, his editor, work to deepen it – and in fact, Mangenot’s work is tight and elegant – the sixteen-year odyssey in Les Cowboys lacks the sense of its predecessor’s scale. The span across decades, from the early nineties to the attacks on the World Trade Center to the London Bombings of 2005, that it intends to portray feel too much like they were shot in the same thirty days in and around modern day France. Bidegain, Ford, or Wayne completists, I advise you: blame it on the budget.

Sean, I received this today and have begun reading. I looked back to see what I missed from you and the only thing I can find it was June 2 , Your article about” Almost Holy”. Am I missing something – XO XO

On Friday, July 15, 2016, CineMalin: Film Commentary and Criticism wrote:

> Sean L. Malin posted: ” Directed by: Thomas Bidegain Written by: Thomas > Bidegain, Noé Debré From an Original Idea by: Laurent Abitbol & Thomas > Bidegain Starring: François Damiens, Finnegan Oldfield, Agathe Dronne, > Iliana Zabeth, John C. Reilly Produced by: Alain At” >

LikeLike

Yes. I e-mailed you more article from the Austin Chronicle. But thank you for reading this one. That’s nice.

LikeLike