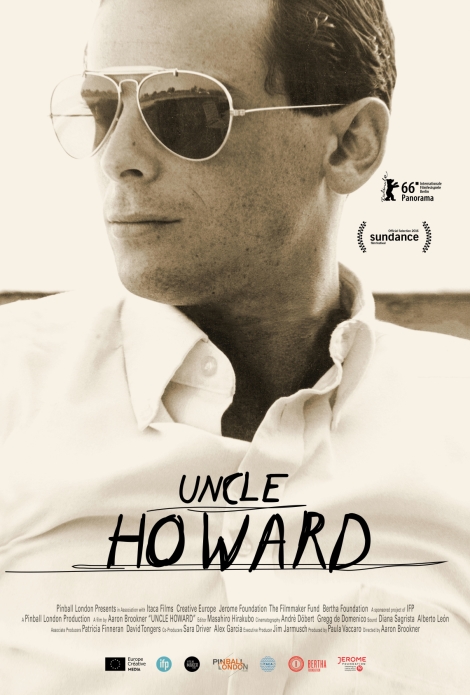

Uncle Howard (2016) – a Pinball London production.

Directed by: Aaron Brookner

Concept by: Aaron Brookner

Featuring: Aaron Brookner, John Giorno, Jim Jarmusch, Tom DiCillo, Sara Driver, Brad Gooch, William S. Burroughs, Patti Smith

Produced by: Paula Vaccaro, Sara Driver [co-producer], Alex Garcia [co-producer], Patricia Finneran [Associate Producer]

Executive-Produced by: Jim Jarmusch

Cinematography by: Gregg de Domenico, André Döbert

Music by: Jozef van Wissem

Editing by: Masahiro Hirakubo

*****

It goes without saying to our readers, I suspect, but so much of the pleasure of contemporary filmgoing is contained in the phrase “Jim Jarmusch.” To see this name in the credits for Uncle Howard (which Jarmusch executive-produced and appears in) is itself a vindication of the talent of its director, Aaron Brookner. It’s not just any wayward, desperate film school grad that gets the seal of approval from both the King of Cool and the Queen, co-producer Sara Driver. After all, these are two of the preeminent independent filmmakers of our lifetime, their combined ratio of masterpieces to sloppy experiments as strong as the Coen Brothers, Akira Kurosawa, or Michael Haneke.

No surprise, then, that this director’s documentary debut is a riveting and beautiful biography on the short life of his late uncle, Howard Brookner, edited with unusual power by Masahiro Hirakubo. I’d never seen hide nor hair of either Brookner, despite the fact that the elder made three major films: Burroughs: The Movie, a Criterion Collection-approved documentary about the late life of its namesake; Robert Wilson and the Civil Wars, with appearances by Philip Glass, Heiner Muller, and theater legend Wilson himself; and the lost-to-scorn Bloodhounds of Broadway (starring Matt Dillon, Randy Quaid, and Madonna[!]) Having respected his uncle so deeply, Nephew Brookner asks and answers the question of how someone on the up-and-up so quickly disappeared into the ether of la cinema esoterica. The answer is both a tremendous tragedy and a true New York-in-the-eighties cliché.

Directing from his own concept, Brookner and Hirakubo walk us through Howard’s experiences at film school, where he flourished quickly and befriended Spike Lee, Tom DiCillo, and the young Jarmusch. The elder Brookner developed some of Burroughs (with DiCillo ultimately photographing and Jarmusch sound-recording) while still at NYU Tisch, early evidence of his undeniable talent and go-getter spirit. He appears in archival footage as spry, gregarious, and ambitious: the Ur-“Nice Jewish Boy”. Appropriately, he was in cahoots with Hollywood by the time he made his third film – his first fiction – in 1989. But as Aaron reveals in his narration, Howard was HIV-positive and exhibiting symptoms of illness during the shoot. He died the year of its release.

Jumping off thirty years later from this revoltingly early death, Aaron becomes inspired to document the attempted recovery of Uncle Howard’s prized film negatives, which remain suspiciously in the possession of the poet John Giorno. We see in the film how, with emotional support from Jarmusch and Driver, as well as Howard’s former partner Brad Gooch, the living Brookner finally gains access to footage from Burroughs, Robert Wilson, and Bloodhounds. As a trained archivist myself, I derived great and immediate satisfaction from seeing Jarmusch and his young protégé open the canisters to discover – miraculously – that these unprotected films had yet to be eviscerated by Vinegar Syndrome.

In that scene, we see the complexities of Uncle Howard, a film about saving film for its inherent value: as memory-keeper, as historical landmark, as Horcrux for its creators. Thankfully, Aaron is not interested simply in recapturing his talented relative’s career and the man’s untimely death, a focus which might have made this no different than Janis: Little Girl Blue or any number of stodgy biographical docs. What Brookner and his collaborators, including Jarmusch, Hirakubo, and the cinematographers Gregg de Domenico and André Döbert, are after is a more evolved testament to the importance of preservation and protection, the arts and artists, in American culture.

Aaron smartly garnishes his own movie with this footage, some of it newly restored and all of it gorgeous. This, I feel, drives de Domenico and Döbert to shoot young Brookner and DiCillo in medium-wide shot, both filmmakers marveling at a desktop computer about the important figures Howard captured in Burroughs (Patti Smith, Frank Zappa, Laurie Anderson.) We see childlike joy and intimate sadness come out of them in this way, all in front of the footage itself. It is also, for example, why this film pays attention to the minutiae of Aaron’s search for Howard’s films, held hostage by Giorno and finally released for our gratitude and pleasure. In recent, more ham-fisted films like Tickled, the narrator’s investigative search for archival material plays for quick laughs; in Uncle Howard, it is for a more noble (and national) historical goal. After all, between Smith, Zappa, Burroughs, and Robert Wilson, we have images of four of the most important artists in the lifetime of our country; who among us does not wish to save every little piece of their archives?

That unexpected historicity and value girds the entire film, though we are far from the formalized aesthetics of Jarmusch’s or Driver’s films. Brookner does utilize interesting visual flourishes, like double-exposed shots which layer gay-bashing imagery and antique photos of 1980s New York, or the truly lovely restored Burroughs footage. But the most impressive accomplishment here is in Hirakubo’s editing, which connects multi-format film and digital film footage into a fluid, unnoticeably ever-changing movie. (Neither drastic aspect ratio jumps nor sound drop-off disturbs Uncle Howard’s pace.) Brookner himself, whose own quite independent career has taken him between fiction and documentary, prioritizes clarity over experimentation for the most part here. This is to his benefit: with its affiliations to Jarmusch and DiCillo, it earned the film premiere berths at this year’s Internationale Filmfestspiele Berlin and the Sundance Film Festival (where it was nominated for the Grand Jury Prize for Documentary.) Since then, it has toured internationally, most recently screening at the New York Film Festival this past Monday, and a more perfect venue I cannot imagine for this film.

The only question that remains is where this documentary, which awaits a theatrical release date, goes now: straight to the pile of ephemera on Netflix? Perhaps into a university’s archive? Or will Aaron, like his uncle, disappear unfairly into the black hole of lost independent cinema? One can only pray that the influence of Jarmusch, whose films are themselves among the most wonderful in history, can keep the Brookners’ collective work somehow alive. We need it.