Directed by: Stanley Nelson, Marco Williams (co-director)

Written by: Stanley Nelson, Marcia Smith

Produced by: Stanley Nelson, Cyndee Readdean, Stacy L. Holman, Marco Williams

Edited by: Kim Miille

Cinematography by: Antonio Rossi, Josh Bagnali, Peter Hutchens, Garland McLaurin, Naiti Gámez, Thomas Kaufman

Music by: Tom Phillips

Official Selection of the 2017 Sundance Film Festival

*****

“Let laments swell the breeze

And wring from all the trees

Sweet freedom’s song.

Let laggard tongues awake,

Let all who hear partake,

Let Southern silence quake,

The sound prolong.”

-W.E.B. Du Bois, “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee”

*****

In 2014, I visited Tougaloo College in Jackson, Mississippi on a grant to dig through some film archives in the American South. At the time, my research focus was on avant-garde film; and my goal was to find footage that interlaced the polyphonous histories of the South with that of American experimental cinema. I didn’t find as much material as I would have liked, but what I found was extensively nonfiction in genre and transgressive in theme. In drawing from Tougaloo’s archive of social activist documentary material, I concluded, “that the avant-garde of the American South can and should be more widely valued as a culturally powerful, pedagogy-combatting element in the nation’s media history.”

Last month, I saw a new feature-length film that strays as far as possible from experimentation, but proves the same point with both vigor and archival expertise. Tell Them We Are Rising: The Story of Black Colleges and Universities, a PBS and ITVS-produced film with additional funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, had its World Premiere at the Sundance Film Festival. While I can’t for the life of me see how this project’s financial profile fits the “independent” narrative that Sundance has tried so carefully to cultivate, its kinetic energy and ideals represent the highest caliber of craft. Ultimately, what the filmmakers lose from their overdependence on classic nonfiction clichés is made up for in political engagement.

This may be the most perfect, most urgent moment for such a film in fifty years – even more timely than the previous documentary from director Stanley Nelson, The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution. Where that Peabody Award-winning film demonstrated an empathy with the earned anger of the Panthers, here Nelson delivers a far more poised and stately dissertation on American history.

Working from a script with co-writer Marcia Smith, Nelson portrays the backdrop for the emergence of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) in the U.S. as a post-Civil War war-zone. African-descended Americans, empowered yet fearful in the wake of slavery’s end, pushed for spaces safe from abundant lynching and race crimes. In this tense environment – and with the pronounced support of many churches, the federal government, and rare Southern white philanthropists – sprouted HBCUs like Tougaloo, Morehouse College, and Shaw University, the first of its kind to be founded in the postbellum period.

The history itself can be easily Wikipedia searched, but remains, like all civil rights landmarks, an under-told and intentionally erased segment of our national narrative. Distressingly, Nelson, Smith, and co-director Marco Williams make some unfortunate mistakes on the way to recovering this history for all-and-sundry.

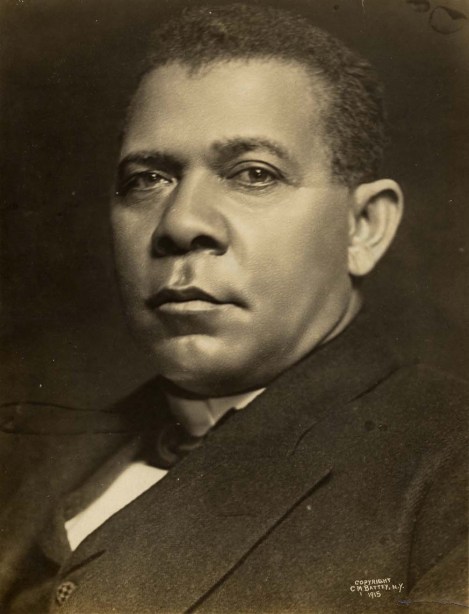

Their first is to assign voiceover artists the roles of leading activists like Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois. Washington’s ability to forge relationships with the wealthiest men in America (the film name-checks Peabody and Rockefeller, among others) brought tremendous attention to the mistreatment of black Southerners of the period. Later, Du Bois would turn learned experience into internationally-read poetry and prose, each work an instructional document in the fight for social equality. The filmmakers choose to superimpose the briefest excerpts of these men’s thoughts over photographs of them at random times. How better to undermine the impact of these community leaders, advocates for justice, and renowned orators than to have their quotes recited with the same stentorian tone used by film trailer narrators.

Equally distracting from the film’s cerebral storytelling is its reliance on talking-heads. Punditry in the modern media landscape is one of its most obnoxious qualities, dulling the value of discursive political conversation (see HBO’s Real Time with Bill Maher) with contrarianism, hostility, and outright trolling. Yet Nelson and Williams, in an admirable effort to avoid unqualified celebrity opinion-sharing, interview civilians with all manner of expertise on HBCUs, including: former and current students; nationally-recognized historians; and civil rights activists.

It would be inappropriately hurtful to be specific here, but several of these individuals proceed down tangential paths, either telling overlong personal stories or repeating themselves. There is an almost defiant lack of professionalism to a select number of scenes which results in a paradox for those in the audience. On the one hand, we respect the directors and their researchers for finding real people to speak to, and for creating the environment of security and confidence necessary for their stories to be told. On the other hand, these moments result in an ineffable slackness throughout the film’s second and third acts, slowing down cinematic locomotion for minutes at a time. Most unfortunately, this effect is a widespread symptom of production within the PBS model (even Black Panthers, a magnificent film, suffers from it).

Thankfully, while the humanism these filmmakers show their participants has narrative consequences, the more heavily archival segments recover much lost propulsion. Editor Kim Miille shows enormous aptitude for juggling three or four images on the screen at the same time without losing the historical theme, qualifying her equally to cut 24: Legacy or Rashomon. Miille slips as many as half a dozen edits into a five-second scene, interchanging side-wipes and diagonal screen-slicing simply for visual stimulation. In the wake of this year’s documentary Oscar frontrunner, O.J.: Made in America, I had not expected to see another nonfiction work that so broadly contextualized and investigated “known” racial history without dropping the ball on contemporary themes. Astoundingly, for all its expansiveness, no single loose thread upsets the cohesion Miille finds within this two-hundred-year-old web of information. This film is bound to have a long life as a teaching tool, but its most exemplary instruction will undoubtedly be on behalf of editing students.

That’s not to take away from the directors and writers, who successfully recast the national import of HBCUs in a modern light. Although civil rights films are increasing in visibility now, with 13th, Loving, and I Am Not Your Negro joining O.J. as Academy Award nominees, not every attempt to contemporanize the movement results in good cinema. Tell Them We Are Rising manages that Holy Grail of documentary feats: to lecture without draining the audience’s trilateral taste for intellectual pleasure, entertainment, and moral approval. Nelson, a Macarthur Fellow and Emmy Award-winning director, and his company Firelight Media, specialize in this kind of work, but it still comes as a surprise when an American filmmaker can make us revel in a history lesson.