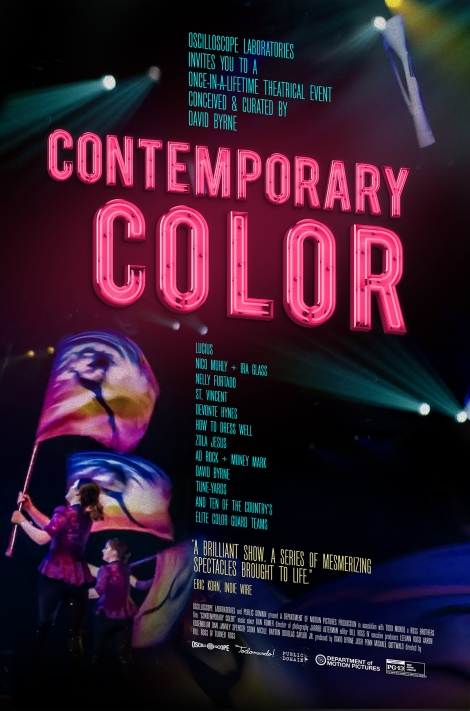

Directed by: Bill Ross IV, Turner Ross

Featuring: David Byrne, Nelly Furtado, Merrill Garbus, Ira Glass, Nico Muhly, Adam Horovitz, St. Vincent, How to Dress Well, Lucius, Devonte Hynes, Zola Jesus, Money Mark

Featured Teams: Emanon (Hackettstown, NJ), Alter Ego (Trumbull, CT), Mechanicsburg High School (Mechanicsburg, PA), Field of View (West Chester, PA), Les Eclipses (Longueuil, Canada), Brigadiers (Syracuse, NY), Shenendehowa High School (Clifton Park, NY), Black Watch (Mount Laurel, NJ), Ventures (Kitchener-Waterloo, Canada), Somerville HS (Somerville, NJ)

Produced by: David Byrne, Michael Gottwald, Josh Penn

Cinematography by: Jarred Alterman, Bill Ross IV, Turner Ross

Editing by: Bill Ross IV

Music Editing and Mixing by: Dan Romer

An Oscilloscope Laboratories release. Now available on iTunes.

Official Selection of the 2016 Tribeca Film Festival

*****

To watch Contemporary Color is to give yourself over, in spirit and sight, to the vortical kinesis of experiential psychedelia. Put another way, it is a trip through a rabbit hole of such eccentric richness that only David Byrne could have ushered it into existence.

I had not planned to write about this film since missing its (very limited) theatrical release in March, but last week, an unexpected event pushed me to revisit it with eyes open: the death of Jonathan Demme.

As I wrote for Paste, I had a brief personal relationship with Demme, whose films changed the face of American cinema and defied genre expectations. Many – myself included – consider his most profoundly influential gift to pop-culture to be his rockumentary Stop Making Sense (1984), about the Talking Heads. When Demme passed away, I immediately felt I needed to revisit the movie and was thrilled all over again by the immensity of David Byrne’s charisma.

Watching Contemporary Color, which Byrne produced and appears in, one cannot help but recall Demme’s movie; in fact, the two, though more than 30 years apart, are in constant dialogue. There is the undeniable matter of genre, which is trampled in both films by novel visual approaches but which remains, for our critical intents and purposes, that of the “concert film”.

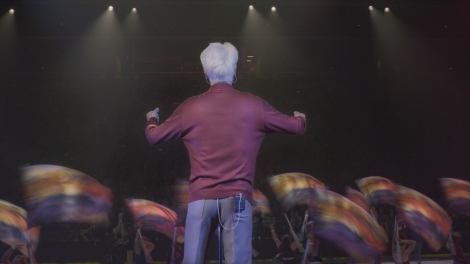

And in both cases, Byrne is the electric center of an already hyperactive atmosphere, his dexterous comic stage presence as earnest as it is supportive of the other artists present.

Furthermore, these films also share a generous relationship to their secondary and tertiary characters, though this has more to do with the stylistic similarities between Demme and the directors of Contemporary Color, Turner Ross and Bill Ross IV. The many cameras each filmmaker employed find enormous amounts of faces.

As I noted in Paste, this was common in Demme’s films: he often sought the most sympathetic close-ups available to his cinematographers, especially in Stop Making Sense, where he got uncomfortably near Byrne while he was mid-performance.

That legacy lives in on with the Ross brothers, who honed their humanistic portraiture skills in highly acclaimed independent documentaries like Tchoupitoulas and Western. Their new film is in equally large part a collection of colorful, intimate close-ups, with the odd multiple super-imposition to heighten the sense of scale.

In the context of a music doc, dozens of shots of tremulous faces, rigid legs, and rifle-swinging arms might seem bold in their experimentation. But they are a necessary ingredient for this feature about color guard performances, which Byrne helped to stage in New York with the participation of several indie rockers and, bafflingly, Ira Glass.

A “color guard documentary,” (it’s hard to consider this a genre with much precedent) like a dance film, presents a tremendous challenge in terms of coverage. Unlike in classical dance, however, the presence of musicians like St. Vincent, Zola Jesus, and Merrill Garbus of tUnE-yArDs requires additional attention – they, too, are on stage with the high schoolers and troupes from that Byrne recruited around the East Coast. How best to provide the appropriate respect to both the color guard performers and to the rockers?

To meet this problem, the filmmakers hired a coterie of independent cinema’s most prodigious and respected filmmakers to capture it: Robert Greene (Kate Plays Christine), Sean Price Williams (Queen of Earth), and Wyatt Garfield (Ping Pong Summer) are all credited as camera operators.

And the filmmakers themselves, like Demme in Stop Making Sense and Martin Scorsese before him with The Last Waltz, formulate a highly complex visual schematic of choreographed camerawork and fluid, river-like editing.

This may sound like a juxtaposition – fluidity versus precision, spontaneity versus polish – but it is intentional. Though the camera captures many a flung object, a teary face, and a bright Byrne smile, the film flows on without pause, defusing any sense of anthology or separation between the performances. That way, no one performance can be considered less polished than another, and the film cannot be accused of being “the sum of its parts,” a la Paris, je t’aime.

By any standard, the final film is top-heavy with footage, dozens of camerapeople following every participant’s movements from the hours before the show (at Brooklyn’s Barclays Center) right through to the exhausted end. Cutting between sequences like a man walking through a thick fog, Bill Ross adds a natural haze of ardor to the proceedings that is lit like a neon carnival. Every image is beautiful, even the ones – like Byrne walking alone with a whistle and a skip – meant to pop with sincere humor.

Larger in scale than any of the Ross’s previous films as directors, Contemporary Color does not feel precisely in line with the vérité quietness for which they’ve become well-known. One gets the sense that their director-for-hire relationship with Byrne is friendly, if distant; there are no revelations, or even discussion, with any of the famous performers they follow.

But there is an immensity of emotion that this film shares with its predecessors, here brought on by the sight of hundreds of enthusiastic, devoted artists performing with utter abandon (flood-like sweat is as prominent a visual element as the kaleidoscopic makeup or elaborate costumes.) In this way, whether Demme was on their mind at the time or not, the Rosses honor the pop-culture legacy of America’s great journeyman director.