Directed by: Zeva Oelbaum, Sabine Krayenbühl

Featuring: Tilda Swinton, Joanna David, Andrew Havill, Simon Chandler, Helen Ryan, Paul McGann

Produced by: Zeva Oelbaum

Executive Produced by: Denise Benmosche, Elizabeth Chandler, Ashley Garrett, Ruedi Gerber, Alan Jones, Thelma Schoonmaker, Tilda Swinton

Music by: Paul Cantelon

Cinematography by: Gary Clarke, Petr Hlinomaz

Edited by: Sabine Krayenbühl

Winner – Audience Award, Beirut International Film Festival

*****

You’ve heard this story before, of course: an adventurous, extraordinary woman accomplishes history-making deeds, only to have her personal narrative suppressed by the world in favor of her more influential blonder male colleagues.

The commonality of this trend is part and parcel of Letters from Baghdad, an earnest documentary restaging of the mythic life of explorer Gertrude Bell. Though devoid of the high desert glamour which Werner Herzog exploits in his recent Bell biopic Queen of the Desert, this nonfiction feature (from co-directors Zeva Oelbaum and Sabine Krayenbühl, who edited) treats its subject with a similar sense of appalled admiration: in both films, reverence for Bell goes hand-in-hand with the suggestion that T.E. Lawrence’s mansplaining acolytes can eat shit (my words, not theirs.)

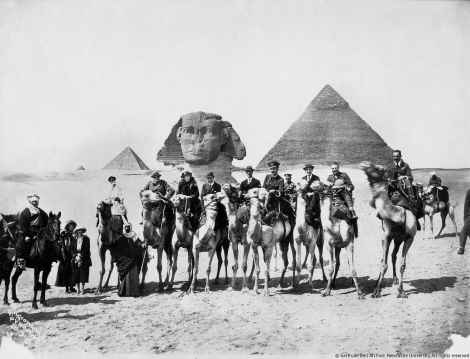

Bell, a scholar of Arab cultures who worked throughout the early 20th century to help install democracy in the modern-day Middle East, was Lawrence’s contemporary; but if this film is to be believed, there was hostility between them. The difference seems to have been stylistic. While Bell was a humanist and an egalitarian, Lawrence suffered from hubris and an aristocratic arrogance that put him at odds with the peoples of the Persian Gulf. He was far from the only male colleague to condescend to Bell (who was left almost completely out of Lawrence of Arabia), and that foundationally sexist antagonism, it is argued here, drove Bell to exceed all expectations of female explorers in Western history.

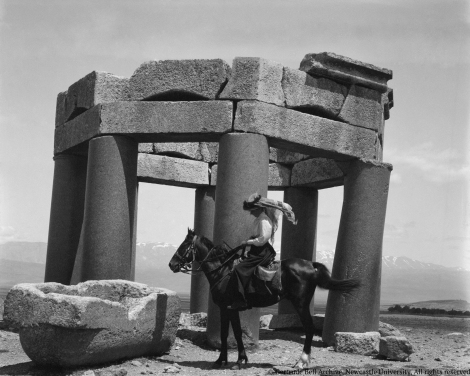

Oelbaum and Krayenbühl’s greatest success is in their determination to make Bell an icon – hers is an under-seen, undervocalized, and underappreciated career that warrants statues in her name and general physical recognition for her accomplishments. Using the explorer’s personal letters, sharp archival stills, and committed voiceover narration by executive producer Tilda Swinton, the filmmakers draw exciting parallels between our inability to recognize Bell by her face and words, and our failure in the West to appropriately acknowledge what she’s done.

In Egypt, for example, she helped to taxonomize, classify, and record the proper names of diverse communities around the country, which would later help local government to award those communities land rights, social benefits, and basic human utilities. Even more famous is her work (with Lawrence) helping to establish the nation of Iraq, installing a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad named Faisal bin Hussein as the first King.

The social relationships Bell formed during this expansive period – which took her from Cairo to Mecca and ultimately, back to Britain, where she died of an overdose of sleeping pills – are represented here through tasteful, if dull, performances. The actors representing Lawrence (Eric Loscheider), Sir Percy Cox (Andrew Havill), and other luminaries from the region speak into the camera with a humorless, distanced energy, so jarring in their stateliness compared to Swinton’s lively and vigorous narration.

A disturbing sense of classicism – not an inherently bad quality – pervades the craftwork here. This does Bell, a thoroughly modern woman for her time, absolutely no favors. Seen through the monochromatic photography of Gary Clarke and Petr Hlinomaz, Allison Wyldeck’s costumes reek of mothballs. Having once worked on a television series set in the early 1900s, I know how challenging it can be to make clothes appear worn, aged, or dirtied on a tight budget. Had this been pulled off successfully, it would have gone a long way towards preserving the antique reality of the filmmakers’ world.

Yet Krayenbühl’s editing follows a strict chronological format that, for reasons I can’t figure out, never escalates in dramatic pressure, emotional violence, or excitement of any kind. Bell’s life, filled with romances and royalty and wars and medals, must have been riveting; yet Krayenbühl recycles footage of landmarks and diplomats smiling so impersonally that these scenes wind up looking like archival stock. All the greater shame considering Thelma Schoonmaker, who is among the greatest editors living and whose best-known collaborator is a fanatical archivist, is another executive producer.

The handsome cinematography by Clarke and Hlinomaz, and the music, by Paul Cantelon, fare better. Cantelon’s studio score is instrumentally simple rather than orchestral, underlying rather than overwhelming (his credits suggest a musical Jack-of-all-Trades). This is appropriate: Swinton’s is a contained and dignified performance anchored by Bell’s wintry appeal, and Cantelon buoys it on a bed of his music.

One (especially when someone is so inadequately versed in international politics as a film critic) hesitates to ask what role Bell’s personal activities played in the wider Middle East’s development over the last century, or specifically Iraq’s. Was she a heroic Odyssean figure, or a Columbus-like “discoverer” who attempted to “civilize” the region?

In Iraq, according to an end title, Bell’s social work is remembered with a fondness and the respect of the literati. But Bell’s legacy in world history is somewhat purgatorial: far from ever being truly forgotten, she is also often elided in our official histories, for reasons the directors perhaps wisely ignore. Despite her evident sense of humanity, Bell remains a figurehead of imperialist stoogery on behalf of the British Empire, admitting herself in the third act that her attempts to place Arab rulers in national power resulted more often in British control.

The answer is lost to history, but Letters from Baghdad insists that it is beside the point. Bell’s greatest accomplishment was to live her life as a 20th-century woman with brio, rejecting the quiet manipulations of men in her field or in her life (her father, we learn through the letters, was her version of The Man) in pursuit of a unique career. No one, especially not T.E. Lawrence, can ever take that away from her.

*****

Ed. Note: Letters from Baghdad opens in Los Angeles and Washington D.C. on June 9th.