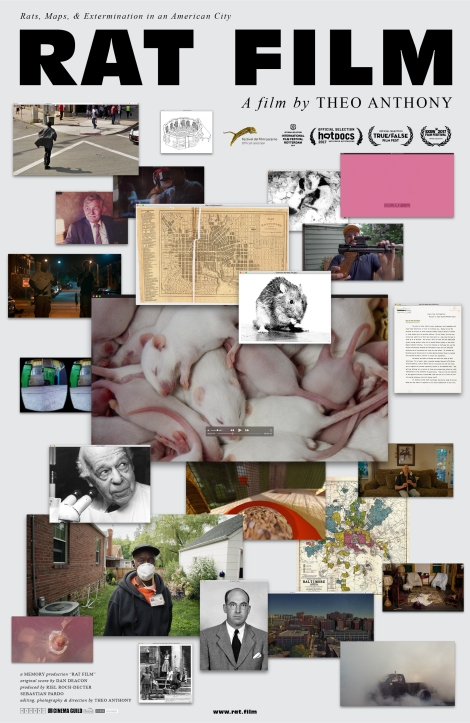

Directed, Written, Edited, and Shot by: Theo Anthony

Narrated by: Maureen Jones

Produced by: Sebastian Pardo and Riel Roch Decter (MEMORY)

Music by: Dan Deacon

Official Selection of the 2017 SXSW Film Festival

“I wouldn’t mind the rat race – if the rats would lose once in a while.”

*****

Plague as a literal fear, and plague as a metaphor, have both been explored with some self-seriousness in recent cinema. For the former, the strongest example is Steven Soderbergh’s beautifully wrought and acted Contagion, a disaster movie where widespread illness originates – spoiler alert – with a bat.

As for the latter, we have Blindness, the misbegotten adaptation of Nobel Prize-winner José Saramago’s novel of the same name. Though the book is among the most intense and challenging parables I’ve ever encountered, the movie physicalizes a plague of blindness which sweeps through an unnamed town as a real disease, rather than what it is: a eulogy, in advance, of the Western world’s forthcoming devolution.

In 2017, Saramago’s predictive warnings (which double as historical remembrances from the author’s home country, Portugal) about the government-enforced collapse of polite society and the feverish spread of acknowledged falsehoods through media channels ring true for Americans more, perhaps, than ever before. Yet the film failed to comprehensively reflect Saramago’s concerns, and instead relied on a frightful earnestness without a hint of the novel’s irony.

A new film from the artist and filmmaker Theo Anthony explores the reaches of plague metaphysically, too, but as a gateway into the structure of a microculture. His setting is the city of Baltimore. His vehicle is the rat, that uber-agent of biological warfare and the locus of much intraspecies hatred. And the plague is humanity.

If you had to classify Rat Film – and you don’t, but I will – you might label it an experimental documentary. The film opens in a dimly lit Maryland alley, where a rat is trying to climb out of a trashcan; over its desperate scratching, narrator Maureen Jones intones some facts about the beast, such as its ability to jump 32 inches. Sure enough, it springs upward, just towards the camera, and as it reaches you…

A sudden cut as Dan Deacon’s blaring music (he composed the score) brings you out of the darkness into a bombastic title card, and away we go. Anthony, who shot, edited, wrote, and directed, uses the disorientation of this moment as his (forgive me) jumping-off point for a motion picture that never stops moving.

Yes, he continues to walk through abandoned streets of Baltimore at the dead of night, where he meets rat-bashing hunters and BB-gun-wielding tough guys. But in the daylight, he brings us to places around the city where the animals are studied, appreciated, and sometimes beloved.

Among the camera’s favored subjects are the veteran exterminator whose catch-and-kill lifestyle has left him with hard-won wisdom; the city’s snake owners, who replicate daily a mass genocide of newborn pups; and Deacon himself, whom we see working with a device that looks like something out of a Da Vinci drawing. Anthony also demonstrates an affinity for scientific and legal minutiae that detours us into several fascinating experiments with rats.

His greatest finds, however, are anthropological, showing us people far more unwelcome in conventional society than the animals themselves. Why is it, the filmmaker asks, that a person who allows rats to crawl on his head while watching television seems insane? And who is that guy playing a flute for his pets?

Their comfort with rats, Anthony suggests, is class-based: the difference between adoring and abhorring them is in large part a matter of your upbringing in Baltimore’s discriminatory culture. It is his history to tell, but suffice it to say that Anthony’s overarching argument begins with the very foundations of the city grid, and has yet to resolve in any way in the modern age. We are still demonizing rats, and each other, as we have for hundreds of years.

Although claiming that racism, classism, and prejudice continue to plague (and to facilitate the literal spread of plague in) an American metropolis is nothing new, the Baltimore-based filmmaker’s multimedia approach encompasses more of his city than perhaps any film has before it.

That may seem grandiose, but consider the range of tools at Anthony’s disposal. Investigative documentary footage is put in conversation with archival material, electronic music, distorted non-narrative imagery, paper maps and atlases.

So overwhelming is this mélange that Rat Film does not so much end as it restates the ever-expanding linkages between human and animal, pest and denizen, plague and cure.

This is literary, expansive thinking, and Anthony, whose work elsewhere includes the Freddie Gray documentary Peace in the Absence of War and a short film, Chop My Money, set in the DRC, corrals his many resources into a project as enjoyable as it is didactic.

Elements of David Simon’s work are there, naturally, but those who come upon the film accidentally – which many will on Netflix, where film festival hits like this one inevitably wind up – may recognize the humanistic verité touch of Les Blank and the research genius of Ken Burns.

Please don’t misunderstand: Anthony’s film is far from imitative, and will upset casual viewers with its avant-gardist cross-cutting. Critics have used terms like “dream-like” or “poetic” to describe the elliptical narrative, but these are too polite: Rat Film is surrealist nonfiction, full stop, set in a nightmare world warped by occultism, mania, and pestilence. Get lost in Baltimore’s Escherian maze of abandoned alleys, and you suddenly enter a city within the city.

A well-known nonfiction writer and professor of mine once told me that what made her favorite writers her favorites were that you could see them thinking as you read. The same must be said of Theo Anthony, whose obvious talents for invention are almost as admirable as his sense of social injustice.

Rat Film, a MEMORY production, is in theaters now.