Directed by: Raoul Peck

Written by: Raoul Peck, Pascal Bonitzer, Pierre Hodgson

Starring: August Diehl, Vicky Krieps, Stefan Konarske, Olivier Gourmet, Hannah Steele, Alexander Scheer

Produced by: Nicolas Blanc, Rémi Grellety, Robert Guédiguian, Raoul Peck

Music by: Alexei Aygi

Cinematography by: Kolja Brandt

Editing by: Frédérique Broos

The Orchard presents La Jeune Karl Marx, an Official Selection of the 2017 Berlin International Film Festival, in theaters February 23 and on demand March 6th.

*****

“Words – lies, hollow shadows, nothing more

Crowding Life from all sides round!”

-Karl Marx

*****

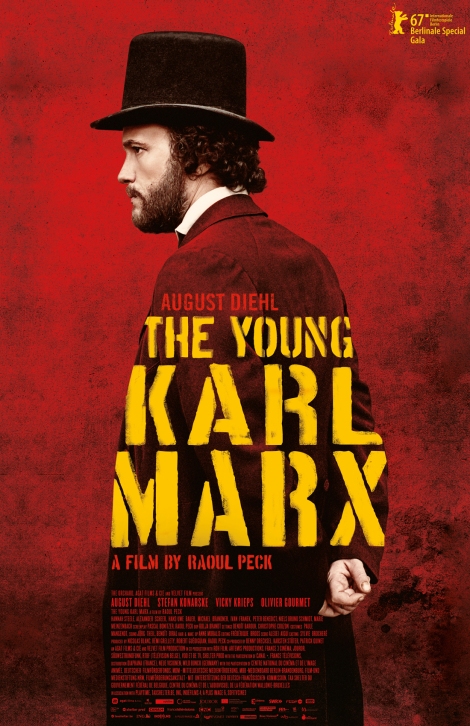

Perhaps the biggest fictionalization in The Young Karl Marx, Raoul Peck’s stately and hyper-intelligent biopic on the early career of the Das Capital writer, is that he was handsome.

As played by the eminently gifted and highly appealing German actor August Diehl (of The Counterfeiters and Terrence Malick’s upcoming Radegund), Marx is an off-Hollywood creation, with sallow cheekbones, a sensitive forehead, and tender brown-lensed eyes. That is the first distraction in this otherwise quite assured picture, which represents Peck’s return to fiction after an Oscar nomination for last year’s genius James Baldwin docu-essay, I Am Not Your Negro.

The second distraction is more welcome: it comes when we see Marx’s wife, Jenny, is played by Vicky Krieps, who burst into my mind and the minds of many filmgoers no less than two months ago when she stole Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread right out from under Daniel Day-Lewis.

Moments after the shock of seeing Krieps in this context wears off, two new questions emerge: Why is Krieps’s exceptional performance not a bigger part of The Orchard’s (the film’s American distributor) marketing strategy; and why has Anderson’s film received all the buzz for what is actually a one-two punch of onscreen genius that includes The Young Karl Marx?

From left: Vicky Krieps, August Diehl, Stefan Konarski. Courtesy Frederic Batier/The Orchard

Of course, I can appreciate that this film is no easy sell based on its title alone, which seeks to (at the very least) humanize and (possibly go so far as to) celebrate a 19th-century German author whom so many hold accountable for the globalized world’s woes. It takes a filmmaker like Peck – an intellectual himself, of rare cultural literacy and social consciousness – even to dare to biographize Marx.

Thankfully, he succeeds within the confines of historical melodrama, though not without sacrificing some of the intensity of I Am Not…

Peck, working from a script he co-wrote with Pascal Bonitzer and Pierre Hodgson, locates Diehl’s Marx some years into his career as a struggling Hegelian philosopher in Germany. Combative and bitchy, he argues with his colleagues about the best way to foment revolution in Europe, receiving unequivocal support only from Jenny von Westphalen, who in Krieps’s interpretation is every bit her husband’s equal.

What the title does not reflect, however, is that the film is a triptych: along with Marx and Jenny, it also observes the Anglo-German manufacturing heir Friedrich Engels (Stefan Konarske, strong) and his wife, Mary Burns.

We see Engels in the moment of his radicalization, when employees of his father’s mill in Manchester (including Burns, brought to vivacious life by Hannah Steele) rebel against abusive conditions. Before long, Engels and Marx are in Paris writing together, a partnership that climaxes in 1848 with the composition of The Communist Manifesto.

Peck, Bonitzer, and Hodgson make several wise choices on the way to that moment.

First, and perhaps most importantly, they treat von Westphalen and Burns with their earned respect. We see early that both women are instrumental to the fomenting revolution, as much due to their ideas as to their support of their husbands (in Jenny’s case, she literally feeds the family.) Any and all historical attempts by the misogynist academic establishment to dismiss these women’s roles are countered by Peck’s story (smart move.)

Both actresses radiate vigor, brilliance, and such intense devotion to the cause of the proletariat that even their husbands sometimes pale by comparison.

An additional element well worth mentioning is the writers’ accomplished handling of Marx’s and Engels’s hyperspecific vernacular.

I am neither a philosopher nor a scholar of European history, so you can imagine that the script’s perfect comprehensibility came as something of a surprise to me. This is Peck’s gift: to make the key characters of our shared history – James Baldwin, Karl Marx, Patrice Lumumba – figures of universally-recognizable humanity. He is among the most clever and most empathic working filmmakers, and The Young Karl Marx is a reminder of both.

So why does the film ultimately seem stale? It has nothing to do with the actors, among whom Krieps, Steele, and Olivier Gourmet – as Marx’s sometime-patron and mentor, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon – are in particularly fine form. The problem, in my estimation, is one of budget.

Olivier Gourmet (far right) as Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. Courtesy Kris Dewitte/The Orchard

James Baldwin in Raoul Peck’s I AM NOT YOUR NEGRO

From the opening sequence, in which a cavalry of haughty landowners slaughters a community of destitute laborers, Peck is operating with one hand tied financially behind his back. Rather than resembling something out of Braveheart – which, for all its problems, is a paradigm of cine-historical spectacle – this massacre looks half-hearted and underattended.

Even Kolja Brandt’s expansive anamorphic crane shots look like imitations of those that might be found in an epic studio blockbuster.

The costuming, hairstyling, and makeup don’t help. Consider that Engels was about 24-years-old when he wrote about the horrific conditions he witnessed at his father’s factory in Manchester. Surely by the time he co-composed the Manifesto, he would have trimmed his beard, or gotten a new haircut? I can’t speak to the real Engels, but I know that my head and face look nothing like they did when I was 24, and that was only two years ago.

Konarske is too impeccably groomed, despite spending all hours of the night drinking and writing and protesting, and dressed to the nines in his tailored suit. You begin to suspect that this might be about the only suit Engels owned. And where did they buy Marx’s henley undershirts – H&M?

The combination of all-too-crystalline digital photography and strangely modern dress is an unfortunate one. It compromises the illusion that Peck has worked so hard to craft, and which he more adeptly captured in small-scale dramas like Sometimes in April.

Engels and Marx. Photo courtesy of The Orchard.

This brings us back to the marketing of this movie, which has been nearly invisible in the United States despite the fact that it opens in New York and Los Angeles this Friday, February 23rd. Marx’s writing is among the most influential in human existence, having inspired whole nations into existence (for better or worse).

Yet there are no reprints to tie in to this film’s release, no speaking events from today’s most respected philosophers, no meet-and-greets with the author’s descendants.

Shouldn’t a biographical drama about his work be the stuff of Oscar bait, with an accented Michael Fassbender at the center? (Diehl is excellent, but he has yet to make the foothold that his role in Inglourious Basterds promised.) Was it Peck, his producers, or his financiers that withheld the possibility of real grandeur from this project?

Hard as it is to speak in hypotheticals, one cannot help wondering what thing might have looked like had Peck received Roland Emmerich’s budget for Anonymous, or even Martin Scorsese’s for Silence. If any film subject demands a decently wide national release and promotional tour, it’s this one.

Only in its conclusion – a montage of scorching political observation in the traditions of Dziga Vertov, Godfrey Reggio, and Spike Lee – does The Young Karl Marx rise to meet Peck’s ingenious creative vision. This is the kind of footage that will one day be shown, newsreel-style, excised entirely from the feature-length drama that preceded it, to students of Marxist thought around the world. I suppose that if this is the film’s only legacy, it will ultimately have been worth it.