Directed by: Steve James

Produced by: Mark Mitten, Julie Goldman

Executive Produced by: Gordon Quinn, Betsy Steinberg, Justine Nangan, Christopher Clements, Raney Aronson, Sally Jo Fifer, Robin Smith, Steven Silver, Neil Tabatznik

Music by: Joshua Abrams

Edited by: John Farbrother, David E. Simpson

Cinematography by: Tom Bergmann

2018 Academy Award Nominee: Best Documentary Feature

PBS Distribution, Frontline, and ITVS present Abacus: Small Enough to Jail, a Mitten Media, Motto Pictures, and Kartemquin Films production. Abacus is available now to stream on PBS.

Kartemquin Films, the independent documentary production banner spearheaded by filmmaker Steve James, has for decades pushed to give a voice to the American voiceless. Whether that term – “the voiceless” – refers to the socioeconomically trod-upon (as in James’s most beloved feature, Hoop Dreams), the victimized (The Interrupters), or the literally voiceless (Roger Ebert biography Life Itself) is no matter to James, who roves among the marginalized in search of classic human interest stories.

The downside to this approach is that each of his (always widely acclaimed) features feels aesthetically cautious to the point of claustrophobia: a Kartemquin production is so unrelentingly traditional that each frame feels like an homage to a thousand films before it.

Such is the case with Kartemquin’s latest, Abacus: Too Small to Jail, which will compete this year for Best Documentary Feature at the 91st Academy Awards, and may win, given James’s renown in the community. If it does, however, it would represent yet another creatively conservative choice from an organization which has fought so hard to appear as anything but.

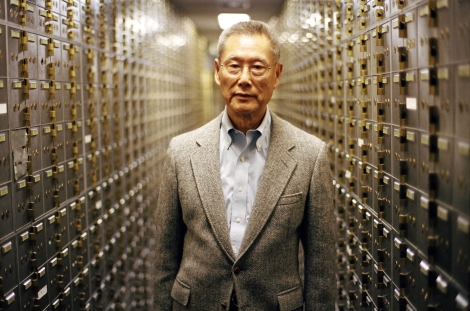

Thomas Sung. Photo courtesy of Sean Lyness/PBS Distribution.

Certainly the story is there. Abacus is a miserable tale of injustice perpetrated against the Sung family, whose Abacus Federal Savings in New York City’s Chinatown was the only bank indicted in the wake of the 2008 American financial crash. After a series of sketchy loan practices was traced back to upper management at Abacus, the owners themselves – including patriarch and founder Thomas Sung, CEO Jill Sung, and Vera Sung, a director at the bank – were publicly accused of mortgage fraud.

James and his cinematographer, Tom Bergmann, spent much of 2015 watching the Sungs as their names were dragged through the mud by The People of New York. In these moments, as Bergmann’s camera discovered their individual cultures and personalities, the film began to reach its greatest heights.

Take, for instance: when Thomas, a composed and stately septuagenarian, gets a haircut, and his fellow-immigrant barber compliments him on his erectness; or when Jill and Vera walk through Chinatown, trying to get the family together for dinner amidst the hubbub of the trial. Bergmann captures their struggle to save face in this period as beautifully, universally quotidian. I mean, who hasn’t argued with their mother about their father’s eating habits?

The case against the business was brought by Cyrus Vance Jr., the District Attorney for New York County, who was himself the subject of intense scrutiny recently for his role in the Harvey Weinstein sex crime saga (Vance Jr. and his team neglected to prosecute Weinstein for a seemingly cut-and-dry case of assault against Ambra Battilana Gutierrez.)

James and his editors, John Farbrother and David E. Simpson, handily turn the Sungs’ humiliation by Vance Jr. and company into a battle between the little guy and The Man, one waged both in the courtroom and on camera.

Why, the filmmakers ask, were twelve Abacus employees photographed chained to one another as they were arrested? And why does Polly Greenberg of the D.A.’s office refuse to call the Sungs “exonerated”, even after their acquittals on multiple charges (this information is public, so please, don’t @ me)? Is the phrase not “innocent until proven guilty”?

The film suggests that the state’s need to make an example of Abacus may have been rooted in racial stereotypes, with the prosecution offering a not-so-subtle critique of non-Western banking practices in legalese.

Or perhaps, another theory goes, the case was borne from the state’s abject guilt at its failure to penalize the actual institutions directly responsible for the financial crisis. You’d think no one in the District Attorney’s office watched Too Big to Fail.

Still, these filmmakers are nothing if not judicious. James interviews Vance Jr. and other members of his team (including, in a moment of outrageous coincidence, a former employee, Chanterelle Sung, who is Thomas’s daughter), even staging call-and-response questions between representatives of the state and the Sungs’ lawyers, Kevin Puvalowski and Rusty Wing. Farbrother and Simpson thread these interviews in with the trial, which is staged as a series of voiceovers and court drawings, fairly seamlessly. Theirs is the most innovative technical work in the movie.

Jill Sung (left), Vera Sung, and Thomas Sung. Photo courtesy of PBS Distribution.

A more invested, perhaps even aggressive documentarian – Errol Morris, say, or Joe Berlinger – might have found genuine tension in the trial narrative and the fate of the Sungs, despite the outcome. With James’s unfortunate evenhandedness comes an avoidable critical distance, and the arm’s-length gap between filmmaker and subjects is this movie’s downfall.

James’s impulse to honor the people who gave him their time drains all passion – and therefore all the entertainment – from the film. Fellow docu-journalists might recognize this as an aspirant objectivism, with the filmmakers trying to give the New York DA his fair share of time. A disturbing end credit even thanks Vance Jr. for his participation in the film. Should Michael Moore have thanked Charlton Heston for appearing in Bowling for Columbine?

I admit that in my mind (and for all I know, in James’s as well), there is no such thing as objectivity in nonfiction film, just as there can be no such distance in cultural criticism. Our concepts of good and bad, tasteful and trashy, interesting or boring, all extend from personal convictions that are as fluid, flexible, and full of hot takes as lava. Even that dad-joke of a metaphor will make some readers laugh, while others will never return to CineMalin (and I appreciate the patronage of both groups.)

But in my experience, well-researched, scholastic documentaries need not balance social concerns with a need to be stately or polite. Morris’s The Thin Blue Line is as angry as a justice-minded film can be, and the director’s immersion in the legal case at its core went deeper than any filmmaker’s before him.

By the end of Abacus, James and Bergmann have spent hours with the entire Sung family, in repose and at work, walking the streets of New York and eating at their favorite restaurants. Yet rather than cry “shame!” at the erroneous miscarriage of American justice perpetrated against them, James photographs the Sungs smiling in the courtroom, triumphant in the face of their years-long trauma. It is clear that they have survived being scapegoated by the District Attorney, despite their images being soiled and their business threatened in the name of commerce.

Concluding on such an upbeat note may be for the benefit of the damaged Sungs, but in the context of our current era, such a conclusion is as naïve to the real consequences on the family and their business as it is unrewarding for the uninitiated viewer. A more cynical tone would have been appropriate, but that would have required a more serious filmmaker.

The sung Family. Photo courtesy PBS Distribution.