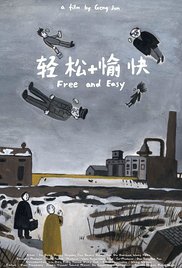

Directed by: Jun Geng

Written by: Jun Geng, Liu Bing, Feng Yu Hua

Starring: Xu Gang, Zhang Zhiyong, Xue Baohe, Wang Xuxu, Gu Benbin, Zhang Xun

Produced by: Wang Zijian, Wang Xuebo, Guo Dong, Wu Leilei

Cinematography by: Wang Weihua

Editing by: Guo Xiaodong, Zhong Yijuan

Music by: Second Hand Rose

Official Selection of the 2017 Sundance Film Festival – World Cinema Dramatic Competition

*****

“Old worn out clothes and shoes,

I don’t pay no union dues,

I smoke old stogies I have found short, but not too big around

I’m a man of means by no means – king of the road.”

*****

Free and Easy is probably the funniest arthouse indie about a fake monk ever to be filmed in Northeast China; at the very least, it is the driest. Like Fargo as directed by Tsai Ming-liang, Hong Kong-based writer/director Jun Geng’s excitingly handsome new feature may be destined for obscurity in American cinemas. But if its recent acclaim at Sundance, where it won a Special Jury Award for Cinematic Vision, is any indicator, a cult of curious cinephiles could choose to commodify this con-artist-centric comedy for continued chortles.

The title is the first of many little jokes crafted by the hyper-droll filmmaker, whose characters’ lives are not only extremely difficult, but also require constant thieving and hustling simply to survive. The worst perp is a wide-eyed, snide salesman (Zhang Zhiyong) whose con involves tricking people into smelling a chloroform-like soap – “a different scent on all four sides!” But in the mopey town where he begins viciously robbing the elderly and the mentally handicapped, he has nefarious peers: a quietly demanding monk (Xu Gang) hawking pendants; two droll police fond of pranking one another; and a few beef-eating highway robbers, to boot.

Jun Geng pushes these amateur delinquents into soft conflict with one another, creating a zone of malice-less danger. Defy the monk, and he’ll put a painful little curse on your family; ignore the soap salesman, and he’ll make you lay down in a field. None of these men (there are only two women with lines in the film, troublingly) seems to want to hurt one another – they just need some money to scrape by and, maybe, a soupçon of adrenaline. In the press notes for the film, Sundance described it as a “Jarmusch-esque” caper, which would be accurate if Jarmusch was directing on crutches. Free and Easy is so laconic, so slowed down, that even when the criminals and the cops get into a gunfight, the fastest-moving items onscreen are clouds in the nearby mountains.

Wang Weihua’s luminous cinematography brings out the best in those gorgeous peaks, further confusing the situation’s ridiculous outcome while marking the film as one of the most beautiful to premiere at this year’s festival. It is a visually stunning work, with wide-angle vistas and landscape panoramas coming up against cookie-cutter housing units and goofy close-ups. We feel a definitive, crushing pointlessness in the entire township – nihilism, pathological narcissism, and suicidal tendencies abound – yet we never leave it. To create an all-encompassing sense of the pathetic, the filmmakers cleverly avoid settling on any single individual. Roger Deakins created a similar kind of Job-like visual environment in A Serious Man, but Weihua shies away from the kinetic tension in the Coen Brothers film. What’s left is camera-work that apes the flaccid, empty behavior of its “heroes.”

Without that tension, there is neither a discernible climax nor clear stakes in Jun Geng’s loopy script. Among the characters, there are no familial allegiances, no close relationships, and no real sense of hate or love. Each of the actors, with Zhang Zhiyong a particularly amusing enigma, begin and end every scene with a blank face. Like Ming-liang or Bresson, who also favored robotic performance styles and repressive emotionality in dialogue, Geng has recycled actors from his extensive filmography knowing that he can count on their inexpression. It is only through his characters’ morose, Coens-like wisecracks (and through the Mandarin dialects spoken in their respective films [since I do not speak a lick of Mandarin, I understand these films entirely through subtitles and inevitably miss certain information and nuances]) that this enviably talented filmmaker distinguishes himself from his referents.

The question of whether he will be able to find a constituency of Western fans depends on a larger concern among modern filmmakers: how essential is narrative to the public’s enjoyment of a film? Often a movie that is short on story but high on laughs is dismissed as trifling, no matter the appeal to devoted cinephiles and completists (like myself, for better or worse.) Likewise, this film was never made to be appreciated by the masses, but that does not imply it falls under the “insubstantial” classification lobbed so aggressively at the narrative-lite films of Jarmusch or, for another close comparison, Hong Sang-soo.

On the contrary, there is a heavy humor to Free and Easy that at times portends mass murder, perhaps, or imminent destruction. It would make for an amusing counterpart to John Wick 2, where the encroaching sense of death extends off the victims onscreen to the viewing audience. Like the Keanu Reeves-starrer, Jun Geng’s film treats people as objective obstacles to the hero’s journey: they are to be shot and buried as soon as possible for narrative efficiency. We feel watching both movies that the end is nigh for all people, not just the characters, and we somehow take pleasure in their removal. But as these films draw towards circular non-conclusions, their endings feel like warnings. These stories are to be continued forever, and you may never see the end of the violent, miserable cycle celebrated by these filmmakers.

Under this cloud of darkness, the panoply of stultified and frustrated protagonists use a few simple jokes and an elaborate sense of aesthetic style to position this as luxury cinema. It is a strangely simple approach for how rarely we see this kind of work from modern filmmakers.